From Shakespeare to Move 37

Our perception of creativity changes with time. It reflects our understanding of what it means to learn. Artificial intelligence offers a fresh perspective.

In her essay “Shakespeare and Creative Education,” Daisy Christodoulou argues that our understanding of creativity changes with time. It’s as much a social construct as it is technical and reflects the Zeitgeist. During the (Northern) Renaissance, when Shakespeare wrote his plays, creativity was perceived as some sort of skilled reproduction of traditional knowledge. Creativity was something you exhibited after having gone through serious repetitive practice, akin to the Malcolm Gladwell ten thousand hour argument. Later, during the Romantic period around the turn of the 19th century, creativity became something else. It changed from repetition to a genius flash of inspiration. It’s probably not surprising that this period came after what we today call “The Enlightenment”—the creative person is gifted by a flash of enlightenment, the lonely genius, sitting under a tree on top of a hill, thinking, and suddenly he comes up with a genius idea.

The lonely genius catches a thought

According to his memoir, Werner Heisenberg walked on the beaches of Sylt, a small island in the German North Sea, when he suddenly got hit with an idea, a flash of inspiration that later turned into the “Uncertainty Principle”. This is a good example of what most of us would consider creativity. However, Daisy says that during Shakespeare’s time, creativity was perceived differently. It was more like Gladwell’s idea that you need ten thousand hours to be good at something. Hard, grueling repetition eventually opens doors to new, interesting ways of completing a task. So which one is it? Heisenberg or Gladwell?

First, let’s define creativity. “It’s the process of coming up with new ways of doing something meaningful.”

Christodoulou argues that repetition of short, periodic subtasks eventually helps you develop creative solutions to specific tasks. For example, footballers don’t play whole games but train specific, short drills to eventually become good at playing games. She says, “Creativity is not developed directly”. In order to develop creativity, you must practice other related skills.

Creativity enters a new frontier

Recently, the discussion around creativity has become more heated because of artificial intelligence. Naturally, researchers working on creative machines ask themselves what it actually is that they are trying to create in the first place. Some smart person once said that “in order to understand something, you must be able to program it”. “If I can program it, I understand it,” goes the saying. And AI has actually given us interesting new clues about what creativity could be. When DeepMind developed AlphaGo Zero, an AI that plays the game of Go, they realized that the machine did something very unexpected. In one of the games, the machine made a move—the now-famous move 37—that most experts deemed wrong, if not stupid. They thought the machine had gone off track and would lose the game for sure. As it turned out, move 37 ended up as a genius strike that helped the machine win the game. Move 37 was so novel that no Go expert could even think of what might be the strategy here.

Since then, move 37 has entered the psyche of AI researchers. It’s become a thing. Each time a machine does something stupid, researchers hope that they might have stumbled over another move 37-type event. Sometimes they do; most of the time they don’t.

Here is a quote from Andrej Karpathy, a prominent figure in AI community of Silicon Valley:

“Move 37" is the word-of-day - it's when an AI, trained via the trial-and-error process of reinforcement learning, discovers actions that are new, surprising, and secretly brilliant even to expert humans. It is a magical,…

Move 37 doesn't have a formal definition yet. Most researchers use it for events that are unexpected and yield positive results. Like, for example, when my Tesla chooses a completely different route because the navigation software anticipates traffic jams or ChatGPT offers an unexpected line of code when solving a programming problem.

What does move 37 have in common with Shakespeare? It’s a new form of creativity. It’s neither a reproduction of stubbornly practiced skills nor genius enlightenment. It’s something else. But what is it? In order to answer this question, I suggest we dig deeper into how modern AI systems are trained. But before we go there, let’s pause and ask ourselves whether move 37 is a creative move. In the spirit of the above-mentioned definition, it is “a novel way to do something with positive and meaningful results”. So yes, move 37 is a novel form of creativity exhibited by machines.

How did DeepMind train AlphaGo Zero to create move 37? How are modern AI systems trained? There are two fundamental ways to train AI systems. One is called unsupervised deep learning, and the other is called deep reinforcement learning. Combined, these two methods yield some of the most advanced AI systems of our time. Let’s dissect them.

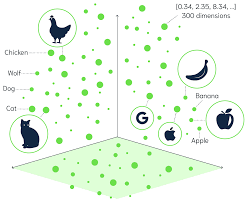

First, unsupervised deep learning attempts to learn relationships between data and store the findings in machine-readable form. The latter typically means some form of vector database, which is convenient for computers to query. For example, the words tree and apple or tree and wood or tree and branch have common ground and relate to each other. Their respective vectors are therefore close to each other, so when the computer queries the database, it finds similarities and relationships between those words. Modern transformers like GPT or Llama crunch trillions of data points to create a gigantic database that stores such relationships between words. When queried, they produce the most probable answer. Note that this type of AI doesn’t explore; it only stores knowledge and then probabilistically produces answers that, on aggregate, are more right than wrong.

But what about exploration? What about creativity? Enter deep reinforcement learning, or Deep RL. Here the model is trying to find different solutions for a given problem. The way it classifies which solution is better is through rewards. Like a child that is given a cookie if she does something well and denied one if she doesn’t, RL is rewarding good actions and sanctioning bad ones. If you do this in billions of iterations, you end up with a model that, when queried, finds novel and hopefully better ways to solve problems. The combination of unsupervised deep learning and deep reinforcement learning yields promising results, and some would argue even creative solutions to problems. Move 37 was made possible by a combination of those two approaches to AI.

Repetition on steroids with a twist

I argue that these insights from AI help us better understand the nature of creativity. It’s the combination of knowledge and exploration. Computers can store enormous amounts of knowledge and run through many iterations until they find something novel, interesting, or, dare I say, creative. Fundamentally, creativity is achieved by both knowledge and lots of trying. And I’d argue that both Heisenberg and Gladwell are examples of creativity. It takes both thinking and experience. Neuroscience teaches us that humans do a lot of information processing in the subconscious. In other words, we do what deep RL does; we iterate over many solutions when confronted with a problem. The “Eureka” moment happens when our frontal cortex, the actual conscious part of the brain, realizes what the subconscious part of our nervous system has already processed. Think of it like a filter that’s designed to make sense out of the many possibilities our subconscious nervous system comes up with. We call this thinking, and the lonely genius does best when left alone on a sandy beach. But thinking alone doesn’t do much. You must have data to process, which is what we call knowledge. So it’s both the genius and the experience that eventually yield creativity.

One of the best examples of creativity at work is Pablo Picasso. In his excellent book “Picasso and the Painting That Shocked the World”, author Miles Unger describes the process by which Picasso developed a new style that today we describe under the umbrella term of Cubism. Unger goes into minute details about how the painter struggles to come up with novel ideas. His mental state is disturbed; he often starts, stops, destroys, restarts, and eventually gives birth to a painting (“Les Demoiselles d’Avignon”) that was way ahead of its time. Creativity, as depicted by Unger, is a grueling process of trial and error. Picasso was a very accomplished painter, with a deep understanding of history, techniques, and contemporary movements in the art world of early 20th century Paris. He was a combination of knowledge and tenacity.

Philosopher David Deutsch makes a similar argument in his fascinating book “The Beginning of Infinity.”. Here Deutsch asks the question of whether there is such a thing as objective beauty. In other words, is beauty like science, something we discover? Deutsch argues that beauty, art, science, and any other intellectual human endeavor fundamentally follow the same creative process of trial and error. He calls it the “trash bin” factor. When Beethoven wrote the Piano Concerto No. 5, he wrote many iterations. Lots of paper ended up in the trash bin until eventually he had a version he liked, a version that subsequently millions of listeners liked, too. Creativity is a process, a combination of experience, knowledge, and relentless persistence.

Here’s the good news: You can train yourself to become more creative

Can creativity be learned? Can it be trained? Can a person get more creative by practicing, like we practice in the gym and get stronger? Yes. If my conjecture is right, then yes, we can practice to become more creative. Our nervous system is like a muscle that can be trained, strengthened, and geared towards certain goals. Some people train themselves to write poetry, others to play piano, and others again to practice martial arts. The same applies to creativity. What’s required is lots of knowledge and lots of iteration. Read, travel, converse, and study as much as you can, and then try lots of new things, and I conjecture you will become more creative.