The Perils of Monetocracy

The Fed is a culmination of expedient solutions to immediate problems that have taken a life of their own. The result is a Monetocracy with no checks and balances.

One small mistake can lead to massive failure. When the Federal Reserve System (Fed) was created in 1913, opposition was loud and fierce. In fact, it was so aggressive that the proponents of central banking had to convene in a secret meeting on Jekyll Island off the Georgia shores to draft the blueprint for the creation of the Fed. But they succeeded anyway, and President Woodrow Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act in 1913. This might just be the single most damaging piece of legislation ever passed by Congress. And if left unchecked, the Fed could eventually bring down not just the US but the whole system of liberal democracies, global trade, and finance. In this essay, we outline the path from conception to the current centrally run fiat system with the Fed at its core. We call this form of government a Monetocracy.

When the Founding Fathers declared independence and subsequently drafted the Constitution, they eloquently articulated the principles of individual rights, liberty, and the idea that governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed. Unfortunately, their ideals didn’t survive. Today, our political system only gives the appearance of legitimate representation of power. In reality, we are governed by a cabal of Fed bureaucrats and political insiders who hijacked the economy and thus our livelihoods through unchecked governance by decree.

Scars are visible everywhere. Our political system is caught in an ever-expanding vortex centered around the Fed, sucking everything in like a giant black hole. Just look at the national debt of over 33 trillion USD. And the spending continues since neither Congress nor the White House are constrained. Whether it’s the left siphoning money through public health channels or the right through the defense apparatus, both sides of the political spectrum are participating in this unconstrained misappropriation of funds and power. We must stop this. But to see the perils of Monetocracy, we must first understand how we got here. In particular, how a complex mechanism of piecemeal legislation brought us to the point where our national debt is larger than GDP and the interest bill alone is one of the biggest items in the federal budget. We will proceed as follows: First, we lay the groundwork by describing the formation of the USA on the pillars of liberty, prosperity, and fairness. Second, we discuss how the creation of the Fed is orthogonal to those ideals, and third, we describe how the Fed slowly crept its way to the center of economic power. Fourth, we present the perils of unconstrained money through the fictitious tale of the Kingdom of Wessex. However, our aim here is not to describe a doomsday scenario but to offer solutions, so Fifth, we discuss possible remedies to the perils of Monetocracy. In particular, we suggest more political competition through segmentation of power and economic influence across the United States. Sixth, we discuss the concept of the “Uncertainty Principle in Economics”. It’s because we cannot precisely reach those goals collectively that we must experiment and try better solutions. Political economy has the same fundamental constraints as any other science; there is a right path, but we will never reach a global maximum. But we must keep trying, failing, and correcting errors. This can only happen if we allow for more competition among states. The monopoly of government must be questioned at every level of constituency and earned. Competition and trial and error are the lifeblood of liberty, progress, and fairness. If we want to increase the likelihood of a better future for our kids, we must bring back more competition in governance and challenge the fiat system at every level of government.

1. An Experiment with Liberty

When the American colonists decided to take up arms against Britain, the seeds of revolution had been sown decades before. It was common practice to disobey orders from the governor because British soldiers lacked the will and means to actually enforce most of the rules. The American colonists got used to the idea of liberty. And even in cases where they were mistreated by the lords, they often just packed their carriages and moved West to conquer new land. While their lives were by no means easy, they still had one big advantage compared to their ancestors in Europe. Geography was on their side. They had access to vast areas of fertile land, and British troops had to be shipped across a vast ocean to defend the crown. This is all to say that liberty is not something American colonists dreamed up by reading books about the Enlightenment. It certainly helped. But the real catalyst for liberty was the fact that they could do it. They sensed liberty, and they liked it.

Thomas Jefferson was inspired by Montesquieu, Voltaire, and certainly by John Locke when he drafted the Declaration of Independence. John Locke, in particular, had a massive influence on concepts such as individual rights or government by consent. But when analyzing the birth of the United States of America, you can’t overemphasize the geographic uniqueness of the place. Another peculiar circumstance was the fact that the colonies themselves had many different political regimes. In other words, the American colonies were a lab for experiments in political economy even before the foundation of the USA. Such experiments are rare and could not be performed in Europe due to entrenched legacy interests. But the US was new and fresh territory. Eventually, the Declaration of Independence was a culmination of ideas, experiments, and experiences that intellectuals like Jefferson eloquently put on paper. But the spirit of liberty was always there. The central argument here is that the souls of early American settlers were drenched in liberty and the pursuit of happiness. And whoever came over from Europe quickly got infected by it. Even mercenaries from Northern Europe, who were brought over to fight for the British crown against the Americans, often deserted and replaced the musket with the plough. “Why fight for an antiquated European regime when the new world offers resources, liberty, and, above all, a chance for the pursuit of happiness?”

Conceived in Space

America was literarily conceived in space. Space both in the sense of geography as well as politically. This is a play of words associated with Murray Rothbard’s "Conceived in Liberty”, a 5-volume narrative on the history of the United States from the pre-colonial period through the American Revolution. Rothbard argues that the availability of space, arable land, and vast energy resources was as important to the creation of the USA as the political philosophy of the Enlightenment. People were given space to pursue their lives without too much interference by entrenched legacy powers. With this backdrop, the country evolved into an economic powerhouse. It’s important to note that nobody deliberately designed a system that would eventually produce the most powerful army and economy the world has ever seen. But the seeds were sown. The US has been a constant laboratory of political, economic, and social experiments. And through that process, slowly, a political system emerged that was superior to anything else.

One small mistake, big risk of failure

But one mistake was made. When Wall Street bankers pushed for the establishment of the Federal Reserve System, political opposition couldn’t stop it. In his excellent book "America's Bank: The Epic Struggle to Create the Federal Reserve," Roger Lowenstein chronicles the political intricacies and rhetoric that led to the establishment of the Fed. Lowenstein leaves no doubt that the Fed was conceived with one goal in mind, and that is to secure the power and privilege of Wall Street. When analyzing the Fed today, it’s worth going back to the beginning. The purpose of the Fed has never been to create jobs or stabilize financial conditions, let alone pursue some of the more lofty contemporary goals Fed officials seem to entertain, such as helping combat climate change. The principle purpose of the Fed was to serve as a backstop for Wall Street bankers.

2. Creation of the Fed - The Original Sin

Lowenstein’s book reads like an elongated article of political rhetoric between two parties fighting for their privilege. On one side were the Fed proponents, such as Wall Street banker Paul Warburg, Senator Nelson Aldrich, and President Woodrow Wilson. On the other side, various political forces were opposing the Fed. It’s interesting how wide the political spectrum of Fed opposition actually was. For example, progressive Republicans opposed the Fed out of fear of corruption. Anit-federalists didn’t want more concentrated power in Washington, and representatives of agrarian states feared the increased financialization of the US economy. However, there is one thing all Fed opponents have in common. They sensed that the creation of a central bank would put too much power in the hands of a few people.

It’s important to consider the creation of the Fed in the context of the time when these events took place. Woodrow Wilson had just been elected president and took office in 1913, the same year the Fed was established. Global trade, transport, and communication saw massive improvements. In the sciences, new concepts such as quantum physics were formulated and opened up a whole new world of reasoning. The established deterministic Newtonian world view was gradually replaced by more complex and novel ideas such as probability, randomness, and conjecture. The more people learned, the less certain things became.

Now, enter bankers like Paul Warburg, who cut his teeth in banking in Germany and emigrated to New York due to marriage. Influenced by the German Reichsbank, Warburg thought the US system was antiquated and lacked the stability of a central bank. He therefore advocated for one and helped design the blueprint for the Fed. His main concern was that market-driven banking cannot be stable without central banking to backstop the system in times of crisis. The Fed was designed to provide insurance against the collapse of banks in times of turmoil. Warburg was right. The US financial system was indeed left to its own devices and regularly collapsed because of a lack of central banking support.

But the price to pay for this stability turned out to be much higher than anybody anticipated. Initially, the Fed was created as a loose system of financial centers. As the name says, the system was supposed to be “Federal”. The initial idea was to keep the US financial system stable by providing liquidity when needed. It took almost half a century for the dam to break and turn the Fed into an ATM for Congress. When Capitol Hill passed the The Humphrey-Hawkins Act in 1978, the Fed received its dual mandate, which added full employment to price stability. Now, under the premise of full employment, the Fed had a legal right to write blank checks for whoever needed them. It didn’t help that only seven years before, President Nixon got off the gold standard. What followed is what economists call “monetization of government spending”. Both sides of the aisle embraced these new powers. President Carter, who presided over the establishment of the dual mandate, welcomed Fed support when delivering social policies, and Ronald Reagan rode the wave of government spending on the defense side. This spending party has continued until today. As a consequence, we have over 33 trillion USD in debt and a massive government deficit.

If money is software for labor allocation, then the Fed has the power to alter the script. It might have taken Congress a while to realize this, but by today, the wheels of institutional corruption and mission creep are in full swing. Today, Fed officials and their dependents in the US Treasury Department openly talk about expanding the mandate to combat climate change or drive social change in the country. Another Pandora’s box opened by the Fed is the involvement in international finance. Today, the Fed is not just “America’s Bank” but “The World’s Bank”. When a Brazilian conglomerate borrows US dollars to invest in local mining projects and suffers setbacks due to a currency mismatch, the Fed steps in to save them. Of course, this happens through obscure indirect channels that even Congress doesn’t quite understand. Most Americans have no clue that this is happening, but the CFOs of international companies are well aware of it and take full advantage. What started as a form of insurance for Wall Street with the formation of the Fed in 1913 has turned into a global ATM for cronies and privileged financiers. And the American middle class is paying the bill.

3. Unconstrained spending is a dead end

Ironically, nobody actually designed the Fed to become a debt monetization scheme. So how did it become just that? The most compelling answer is that the US system was not designed to deal with a central bank. On the one hand, you have Congress, which is granted the right to pass laws and control government spending. Congress reports to the sovereign, which is the people who vote for representatives. No matter how corrupt the system might have become, there is a system of checks and balances in place. Representatives are accountable for spending, even if they believe they’re not. On the other hand, you have the Fed, a group of unelected bureaucrats who have full control over the money supply. The Fed controls banks and issues currency. They effectively control the economy. If a bank goes bankrupt, the Fed can save it. If an industrial company goes bankrupt, the Fed can save it. If the government needs money, the Fed can provide it. The list goes on. Today’s Fed is a culmination of expedient solutions to immediate problems that have taken a live of their own. And nobody actually designed it to be like that.

The tragedy here is that Fed officials are not accountable to anyone. They have created a cabal of like-minded priests who religiously spread the gospel of central banking and its alleged benefits to society. Of course, the priests are not called priests, but economists. They populate academia, Wall Street, and the media. Questioning the gospel is out of question. In some rare cases critics get chastised by the priests. In most cases however, they are simply ignored. Economics, unlike physics, doesn’t need to pass the reality check against nature.

Maybe it’s by design, or maybe it's just an accident of history. But the combination of Congress and the Fed is what is so toxic. Congress is granted the right to pass laws and control spending. The Fed’s purpose is to provide liquidity to the banking system. When isolated, both of these institutions could fulfill their duties without too much damage. But in combination, they become toxic. Congress is supposed to be part of the checks-and-balances institutional framework. If money is scarce, that function actually makes sense. But if you add an institution like the Fed with unconstrained and uncontrollable rights to issue currency, then Congress becomes a suicide mission.

Imagine a world where money is scarce, like gold, for example. Now, let’s assume President Bush wants to go to war and asks Congress for billions to invade Iraq. In a world like that, Congress would ask hard questions since everybody knows that the funds are limited and you better spend them on something that benefits the country. Or imagine the pandemic response under a scarce-money regime. Would Congress agree to lockdown the economy and throw money at idle businesses? It’s fair to assume that this decision would have been discussed much more thoroughly in a scarce-money regime. But unfortunately, we live in an unlimited money regime where the Fed has the key to funds. Under such circumstances, decisions like war, lockdowns, medicare, defense spending, and many more government plunders are just part of political rhetoric with no real substance behind it. While politicians argue about the pros and cons of lockdowns or school closures, the Fed is covering the tap. While ordinary people feel the pinch, the decision makers don’t bear any consequences. Even worse, they feel like they’re not paying for it. Try this experiment at home with your kids. Tell them that spending eight dollars on a Starbucks Frappuccino is a waste. Now do the same under the condition that they have to earn the money they spend. One thing is guaranteed. They will change their behavior in the latter scenario.

If the creation of the Fed was the original sin, then Ben Bernanke was the destructive sequel. It was under Bernanke when the Fed first decided to openly buy bonds in the market and directly support businesses. Bernanke started purchasing mortgage-backed securities from banks to help them survive. This was the first time the Fed openly took the liberty to decide who wins and loses in the economy. It’s hard to overemphasize the audacity of what Bernanke did. By the end of 2008, Congress was debating whether to pass TARP, a program that was designed to bail out the mortgage sector on Wall Street. But Wall Street banks couldn’t wait for the tedious process of democracy and urged Bernanke to just buy the necessary securities from the banks. Thus, the Fed not only circumvented the democratic process of deciding whether funds should be spent, Bernanke also engaged in a hitherto unthinkable act of single-handedly taking matters into his own hands and deciding which banks to save.

And he got away with it. In fact, he even got a Noble Prize. But the real damage Bernanke did was not the trillions he wasted on saving Wall Street. His worst legacy is that he created a culture of intervention at the Fed that successors such as Janet Yellen and, most recently, Jerome Powell took to the next level. Under Powell, the Fed started buying corporate bonds and even junk bonds. Imagine that! The central bank buys bonds from near-bankrupt food retailers, crypto banks, or cement companies. Powell did this in the name of supporting the financial system after the pandemic crisis broke out. The jury is still open about whether Powell is the culprit or a victim here. But what is clear is that his actions opened up a huge Pandora's box.

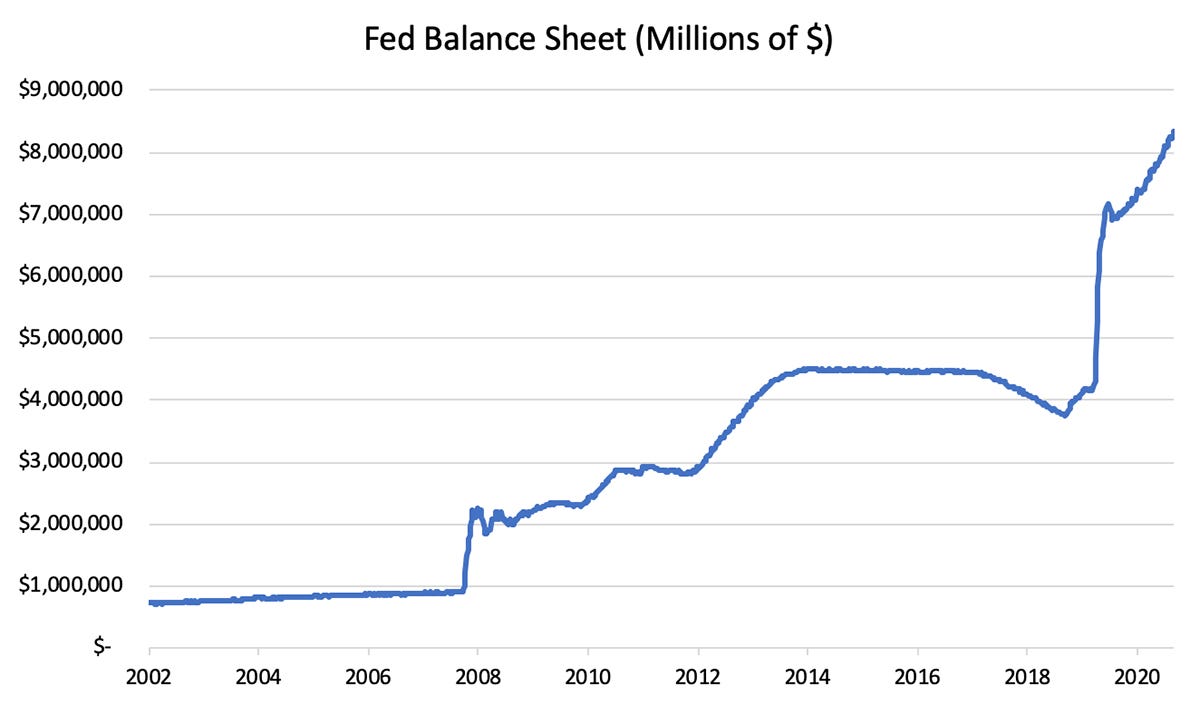

For starters, the Fed now has over 8 trillion dollars on its balance sheet. That is up from two trillion in 2010. A direct corollary of that is the ballooning US government debt and deficit, which is only getting worse. But the worst impact of Powell’s indiscriminate bond buying is the culture of intervention it spreads around Washington. If we can buy bonds to support businesses, why not use bond buying to drive policy? How about buying bonds from companies that engage in carbon capture? Or buying bonds from corporations that declare that over 50% of their officers are women? The sky is the limit here, and creative policy operators are already watering their teeth. And for those who think this is a one-sided misappropriation of power by the left, just wait until the political tides swing in Washington. Then we’ll see politicians propagating the purchase of bonds issued by companies that build weapon systems to protect us against China. One way to design an optimal political system is to assume your worst enemy is in power. Under this scenario, you wouldn’t want the toxic symbiosis of Congress and a free-wheeling Fed openly monetizing politically motivated spending.

Our current political system, with all its checks and balances, falls short of liberty, prosperity, and fairness because it’s being systematically undermined by the Fed. If you let people spend money unconstrained, bad things will happen.

4. The monetary experiment of the kingdom of Wessex - a parody

After he finally defeated the Vikings, King Edward of Wessex was nearly bankrupt. Years of warfare depleted resources and assets. But morale was high. Finally, the Saxons were freed from the northern threat. In order to rebuild his kingdom, Edward needed the consent of nobles, merchants, and craftsmen. Wessex was a flourishing kingdom on the southern shores of Britania, and Edward took it upon himself to rebuild the kingdom after years of warfare. So he called an assembly to discuss the plan.

While the nobles didn’t want to give the king absolute power, they recognized that the only way to protect the kingdom from future attacks was to establish a strong army with clear leadership on top. So, after months of deliberation, a compromise was found. The nobles called it "checks and balances". While they gave Edward executive powers, they constrained his financial freedom. An assembly was to be elected by the nobles with the power to pass taxes and laws and approve spending. Edward could not spend any large amounts of money without approval from the assembly of nobles.

Another important pillar of the Wessex governance structure would be the establishment of a separate assembly that checks whether laws are legitimate. Wessex wanted to use the opportunity of reconstruction to build a system of governance that preserves liberty for its nobles, merchants, and craftsmen. “Anybody who produces valuable goods in the kingdom should be their own king”, one of the prominent nobles proclaimed proudly. A charter was drafted to formulate the key moral and ethical pillars on which Wessex was to be built. This document served as the basis on which an elected assembly of nobles would judge whether the laws of Wessex were legitimate.

Over the next thirty years, Edward led his kingdom to unprecedented prosperity. Craftsmen developed new methods to process steel and helped develop a system of sophisticated weaponry that kept intruders away. Architects found ingenious methods to build roads, bridges, and buildings that made Wessex the envy of kingdoms all over Europe. Commerce was vibrant, and high levels of immigration led to a surge in population.

But not all was rosy. The massive influx of immigrants led to a surge in land prices, which nobles exploited aggressively. They kept land scarce and thus drove prices ever higher. This created several undesired dynamics. First, new immigrants had to borrow funds to buy homes or pay very high rents. Encouraged by high demand, nobles started buying even more land with credit. Money lenders were happy to lend funds to the nobles since land prices only kept going up. “We don’t mind lending when collateral only goes up in value”, one of the leading merchant bankers said.

After Edward’s death, his son, Edward II, took over the reigns of the kingdom. Edward II was well educated and instructed his best craftsmen to find ways to deal with large areas of swamp land surrounding the capital of Wessex. Swamps make land unusable for agriculture and therefore constitute a drain on resources. Heinrich Klaus, a Germanic immigrant with expertise in drainage methods, moved from the Lowlands (today Holland) to Wessex. He was promised work there by John Searle, a noble in the service of Edward II. Searle saw an opportunity to drain areas around the capital and capitalize on the land. Edward II promised him concessions if he managed to drain the swamps successfully. Klaus moved quickly and applied the drainage methods he learned in the Lowlands. After only six months, the first swats of land were successfully drained, and only one year later, settlers started moving in and cultivating the land. Klaus’ methods were so successful that within five years, Wessex saw a massive increase in arable land. “It was a sign of God,", he later explained to Edward II, who granted him the title of a noble. “I used the techniques learned in the swamps of the Lowlands. There is a key difference between Wessex and the Lowlands, and that’s the massive tidal range. Thanks to the highs and lows, we were able to build appropriate dams with porous drainage pipes that would suck the water out at low tide and not let it back in at high tide.” Klaus was so enthusiastic that he helped develop an early version of a university in Wessex. A place for learning and developing new skills.

Klaus’ innovations had a welcome side effect, which is that land prices finally started to come down in the kingdom of Wessex. The added supply of hitherto unusable land put an end to decades of uninterrupted price increases. While immigrants welcomed the newly found affordability, many nobles got into trouble. They had borrowed funds by mortgaging their land possessions and now found themselves in a perilous situation where their collateral was losing value. To add insult to injury, rents also started falling because the increased affordability of land put a lid on rents that landlords were able to extract from farmers.

Deflation in land prices drove many nobles into financial trouble. And since they weren’t able to repay their debts to the money lenders, the financial system of Wessex suddenly began to shake. Edward II was fond of the innovations in land drainage and welcomed the newly found affordability of land. But he also felt the anger of the nobles, whose wealth was dwindling. “We are a land of nobles who take pride in cultivating the land. Now Wessex has turned into a bazaar of immigrants, merchants, craftsmen, and above all, Germanic people, whose magic is turning our kingdom into a circus”, one of the more prominent nobles cried in the assembly. “Sire, we must stop this increase in foreign influx and put a lid on land drainage”, he demanded. But Edward II didn’t want any of this. He refused to put a stop on the prosperity of Wessex just because a few dozen nobles were in financial trouble.

Unfortunately, the prosperity of Wessex didn’t go unnoticed in neighboring countries. King Olaf of Norway always wanted revenge for the loss of territories in Wessex that his father suffered. The fact that Wessex also had the reputation of being a prosperous place where people find happiness made him even more angry. Olaf was the jealous type and didn’t want any of this glory attached to the land his father once ruled and lost in battle. So Olaf put together an army and decided to invade Wessex.

Edward II had the necessary military strength to withstand Olaf’s assault, but defending the invasion cost him much more than he initially thought. So, Edward II was in the same position as his father. He did defeat the Vikings, but the battle cost him so much money that he was at the mercy of the nobles to finance the postwar period. Now the nobles had a bargaining chip they put to use. They wanted Edward II to stop draining land to stabilize land prices. Edward II was still vehemently opposed to this idea.

Paul Maastricht, a banker from the Lowlands who had emigrated to Wessex some ten years ago, was a successful financier in the capital. Maastricht approached Edward II with a proposal. Instead of running the Wessex economy on silver, which was the currency of the land, why not issue paper money and make it legal tender? Edward II was flabbergasted. “Paper money”, he exclaimed. “How can this even work? Nobody would accept paper money.” ”Sire, with all due respect, but if you issue the money with your seal on and make it mandatory for citizens of Wessex to recognize them as bills of exchange, they will accept it. They won’t have a choice. Sire, we tried this in Europe, and it worked. You can issue paper money. If you back it with the full weight of your authority, it will work.” King Edward II was skeptical. He declined and sent Maastricht back to the drawing board to come up with better solutions to finance the reconstruction of his kingdom.

Maastricht, however, was obsessed with the idea of paper money. In fact, he had an even better idea. What if a consortium of bankers controlled the issuance of paper currency on behalf of the king? What if he and his friends were able to secure a position in this consortium? “This is nothing short of a backdoor to power”, he thought. However, Maastricht was not the power-hungry, evil type. He was a god-fearing religious man with ethics. He genuinely thought that paper currency would make the kingdom of Wessex even more efficient and prosperous. After the rejection by Edward II, he went back to doing business as a merchant banker.

Lord Grant, a powerful noble with lots of land possessions in the north of Wessex, had lots of debt outstanding with Maastricht. Grant was desperate. He needed a miracle to save him from bankruptcy. So he sent his deputies for one more negotiation with Maastricht to find ways to settle his large debt with the money lender. Maastricht was not interested in bringing people down to their knees. In fact, it was in his interest to help Grant in order to prevent turmoil in the Wessex economy. Grant’s land possessions were so vast and his debt so large that a default could have shaken the very economic foundations of Wessex. “If Grant goes down”, he told his assistants, “then others will follow. We must find ways to help him.” Suddenly, one of his assistants had an idea. “Why don’t we engage Grant in persuading Edward II to accept the paper money scheme? Edward II was married to Grant’s cousin and thus related to the noble. He might just have enough interest and an ear for Grant.

Next week, Maastricht invited Lord Grant and a number of other important nobles to one of his estates on the coast of Wessex. They convened in order to find solutions to the debt crisis that befell most nobles in Wessex. Falling land prices pushed down the value of collateral that the nobles used to borrow funds from merchant bankers such as Maastricht. Over the next week or so, the group of men came up with a scheme to propose to Edward II. The idea was to create an assembly that is in charge of issuing paper currency in Wessex. Edward II would have the final say over how much currency to issue, but the day-to-day operations would be run by bankers such as Maastricht. If the current debt, which was denominated in silver, could be transferred to paper currency and the central committee controlled the issuance of that currency, then the committee would also have the power and ability to finance debt, save near-bankrupt nobles, and finance future projects with money they don’t actually own. Most nobles liked the idea and agreed to present the scheme to Edward II.

While the king was still opposed to the idea, Grant and others were able to persuade him to at least consider the project. Unfortunately, that same year, King Edward II died suddenly and left the throne to his daughter Elisa. Wessex was not quite ready for a queen, but since the charter clearly postulated that any first-born descendant of the king follows as a new sovereign, Elisa was crowned queen. Wessex nobles were aware of the risk of civil war and wanted to make sure that the question of male versus female heirs didn’t derail the kingdom. Elisa was a strong, well-educated queen. But as with any change, the fact that a queen was now on top created a power vacuum. Greedy nobles saw an opportunity to grab more privilege and play the court game in their favor.

Unfortunately for Elisa, the next few years brought unprecedented weather to Wessex, with storms, draughts, and cold winters. As a consequence, the food supply dwindled, which drove prices higher and made everybody worse off. Maastricht and his nobles saw this as an opportunity to approach the queen with their paper money proposal. They argued that Elisa would be able to finance the necessary purchases of grain and other supplies if she had the power to issue currency. Elisa was skeptical and consulted her advisors, who told her that her father was against the idea. This was all she needed to know. The idea of paper money was nixed again. “I can’t buy grain with paper”, she told a solemn Maastricht, who thought that this time he would manage to convince the Wessex crown to ditch silver for paper.

Elisa was a tough queen. She had to be. As the first female ruler of Wessex, she had to show her iron fist. Think of Maggie Thatcher in the Viking Age. Wessex continued to flourish under her rule despite land prices falling and financial debt ballooning in the accounts of most nobles. One of them was Lord Kingston, an ambitious landowner whose properties were adjacent to the newly drained lands that Heinrich Klaus and his fellow experts were able to claim. As demand and supply go, the value of Kingston’s land declined substantially since the adjacent newly drained fields were much more fertile due to massive oceanic sedimentation. Famers flocked to the new land like flies. “You don’t even need fertilizer here”, one exclaimed victoriously. Millions of years of sedimentation of seagrass, algae, and all kinds of sea animals created some of the most fertile land in the kingdom of Wessex. The land was so fertile that Lord Kingston’s serfs preferred to till the newly drained land and pay their dues that way rather than work on Kingston’s land. Needless to say, Kingston’s properties weren’t exactly in demand anymore. Unfortunately for Lord Kingston, he had engaged in massive land speculation and built himself an ostentatious castle right on the shores of Wessex. All this cost a lot of silver. Silver Lord Kingston didn’t have. And as his land values declined, the lenders wanted more collateral. Lord Kingston was in financial trouble.

After a particularly humiliating dispute with Maastricht, who was his main creditor, Kingston threw a fit and threatened to have Maastricht evicted from Wessex if he kept pestering him for money. “I have powers”, he cried. “I have access to the crown, and I can make sure your petty banking operation gets thrown back across the channel to Europe. Wessex doesn’t need greedy money lenders!” Maastricht, always keen to grasp opportunities, listened carefully. “Powers, you say. What powers exactly do you have? What is your relationship with Queen Elisa and the Crown?", he asked matter-of-factly. Kingston was taken aback. He didn’t expect Maastricht to counter his offense with curiosity. “Well, I am... well, I am connected. What do you care? I am telling you to leave me alone. I am powerful. Don’t mess with Lord Kingston. That’s all you need to know!” But Maastricht wanted to know more. “Sir”, he went on in a calm voice, “if you have the power to expel a prominent banker from Wessex, then you must be a person of consequence. No doubt. Why not use your power for something more productive? I have a proposal.”

Maastricht was by no means an evil character. His demeanor was always optimistic and productive. He genuinely wanted to improve the lives of his compatriots, clients, and, above all, the conditions in his chosen home, Wessex. He firmly believed in the value of paper money and the ability to issue currency. Thus, he saw an opportunity to use Lord Kingston and his connections to make that happen.

The scheme was somewhat intriguing, but Maastricht thought it was worth the risk. “Norway is still keen on fighting Wessex and reclaiming the lost throne”, he said. Lord Kingston was always one for politics, and his face suddenly lightened up in the manner of a man considering new frontiers. Maastricht felt the change in Kingston’s mood and raised the stakes: “Why do we always wait for them to attack us? Why don’t we send troops there and finish this threat once and for all?” ”Ha, you banker! You are a money lender, not a warrior!”, Lord Kingston replied wide-chested.“Your suggestion is absurd. We neither have the ships nor the necessary allies in Norway to land a successful invasion. This would be suicide!” Maastricht kept his cool. ”Only if we do it the old-fashioned way. What if we hired mercenaries from Northern Europe and the Alpine regions? What if we promised them land in Wessex upon successful completion of the invasion?” Lord Kingston’s face suddenly lightened up. In an instant, he understood what Maastricht was after. Maastricht went on, "Yes, sir!" He stamped his fist on the thick oak table in front of them. ”We convince the crown to issue bills of exchange. Bills that can be redeemed for silver, or, and that is the whole point here, for land, What if we convince Queen Elisa to exchange land for land? She takes Norway, and mercenaries get land in Wessex." ”You want to mortgage my land?” Lord Kingston cried furiously. That’s not going to happen. “Well, what if we convinced the crown to mortgage your land at values much higher than today? In fact, what if we valued the land at prices much higher than today's market value? Remember how precious your land was before the Germanic Klaus came and drained all the land around Wessex’s capital? Back then, your land was worth more than double what it is worth today. In fact, I would be willing to take the parts of your land you’re willing to sell at double the market value and mortgage them to the queen. I believe we could make this work. You repay your debt at elevated valuations, I get my money back, the queen gets Norway, and as a nice side effect, we also get an early glimpse of what paper money could do for the crown. Everybody wins”, Maastricht exclaimed with a satisfied but somewhat curious voice. He looked Lord Kingston in the eye and, with a straight face, repeated his proposal. “My Lord, you are bankrupt. You can get out of this with dignity, land, and wealth. All you have to do is help me convince the Crown. And since Queen Elisa is not going to agree just like that, we need a little bit of help. We need her to believe that Norway is about to strike again. Once she is convinced, we suggest to her our plan of counterattack and the way to finance this operation would be through bills of exchange backed by the crown of Wessex and land, not silver, not gold, nor anything else but the good faith of the crown.

Lord Kingston agreed wholeheartedly and immediately set the plan in motion. His agents around Europe started spreading rumors of a planned invasion by King Olaf to retake Wessex. Kingston also paid cronies in Norway to spread the rumor there. It didn’t take much time for the news to reach Queen Elisa. As usual in such circumstances, she convened an assembly to discuss the matter of defense, which in actuality meant she had to raise funds from the nobles to plan her defense. Of course, Lord Kingston was present and took the stage. “Milady, we must change our strategy. Why always wait for the Vikings to invade? Why don’t we send ships to their lands and finish them there? We take Norway, install a benign king, and rid ourselves once and for all of this threat."The murmur spread across the assembly of nobles, who took Kingston’s suggestion with mixed feelings. Some shouted enthusiastically in support of Kingston’s plan, while others expressed concern. The discussion went on, and Kingston eventually managed to persuade the assembly to consider his plan of invasion. On the topic of financing, Kingston mentioned the idea of bills of exchange but referred to Paul Maastricht to explain the details to the crown. Queen Elisa was open to the idea. She was fed up with the Viking threat and feared that it wouldn’t go away if she didn’t actually put an end to the despotic nature of King Olaf. After weeks of deliberation, Maastricht and his merchant banker friends established a scheme that would issue bills of exchange backed by the crown of Wessex. The bills were redeemable in silver or land and used as payment for soldiers. An army was raised, and the invasion of Norway was prepared.

As the newly formed Wessex armada sailed towards Norway with thousands of mercenaries on board, Queen Elisa stood nervously on the pedestal of her royal vessel. She had no intention of just being a bystander. Like a true sovereign, Elisa wanted to take part in the battle. Her role was to coordinate the archery division and launch assaults on the Vikings while her men embarked on the shores of Norway. Unfortunately, luck was not on her side. Due to thick weather, navigation was close to impossible, and the Wessex ships reached Norwegian shores far away from Olaf’s settlements. And if that wasn’t bad enough, the region where Elisa’s army landed was particularly rugged and hostile. There were neither enough provisions nor did Elisa’s army posses the necessary local knowledge to deal with the inhospitable terrain. Olaf’s spies spotted the Wessex army and started guerrilla warfare that decimated Elisa’s troops and hit morale badly. After weeks of strife and suffering, lots of troops deserted, and Elisa was left in a perilous situation. Suddenly, the throne of Wessex was in danger. If Olaf managed to raise a large enough army, he could surround Elisa and wipe her out. Wessex was in existential danger.

A quick decision was made to move Queen Elisa back to Wessex while leaving troops stationed in the vicinity of Olaf’s settlement. Elisa was to return and raise another army to invade Norway. But funds were limited, and the Queen summoned her most trusted financiers to discuss matters. “The nobles in Wessex are tired of funding wars. Gentlemen, if we want to defeat Olaf and put an end to the Viking threat, we must find other sources of funds”, she proclaimed in a somber speech. Paul Maastricht sat in the back of the assembly and summoned his courage to finally speak up. For more than ten years, he had been waiting for this moment to propose a fiat-money scheme to Queen Elisa that would give Wessex the power of paper money. He formulated his proposal in as simple a language as possible. He spoke about the bills of exchange, the land-for-land deals, and most importantly, he added the concept of credit to the equation. “Milady, you can borrow funds by issuing paper money that will be redeemed later with silver from the conquered land. As collateral, you can use land, land that I’d be willing to supply as collateral.” Maastricht saw it all lined up in his head. He kept on delivering the speech of his life, filled with clarity and powered by the enthusiasm of a man overtaken by his own ideas.

Queen Elisa approved the scheme reluctantly. Her hands were tied. She needed troops to go back to Norway and conquer Olaf’s army. So, Maastricht’s monetary scheme was approved and immediately put to work. A centrally governed institution was formed and given the charter of the “Bank of Wessex”. Maastricht was offered the chair position but declined and put one of his best allies in charge. Bills of exchange were issued with the seal of Queen Elisa, supporting their legitimacy. To the astonishment of all but Maastricht, the bills were immediately accepted by the public. One stroke of genius was to declare them as legal tender and guarantee their acceptance as tax payments. Once craftsmen, farmers, and merchants knew they could use the newly formed paper money to pay their dues to the crown, they had no problem accepting it as money. However, convincing foreigners to accept the Wessex bills was another story. When army recruiters toured continental Europe to raise a mercenary army, they found resistance. Why should a mercenary from the northern parts of Germania accept a bill of exchange issued by a foreign queen? Maastricht was informed about the trouble and set out to solve the problem. “Let’s just guarantee them with silver. Let’s set up Bank of Wessex branches across the continent and give the mercenaries the comfort of knowing that they can always exchange their bills for silver." Yes, sir, but if we guarantee their value with silver, we might as well just give them silver. Why go through the trouble of convincing them to accept paper that is fully backed by silver?” One of Maastricht’s employees asked. “Because they won’t!” Maastricht answered while stoically staring at one of the bills on his thick oak table. “They won’t. They will trust us. Carrying silver is an ordeal. It’s much easier to put paper money in your pocket than to carry a chest full of silver with you. They will trust us, and if they start using the bills for payments, then others will trust us, too. If we can establish the bills of exchange as a means of payment across the continent the same way we managed to circulate them here at home, we will have a powerful financial tool at our disposal.” Even if only half of them accept the bills without immediately running to our branches to exchange the bills for silver, we have won. Since that way, we would technically double our availability of silver.” "But sir, that can’t be”, answered a somewhat confused employee. “We can’t just pretend to have double the amount of silver. We can’t create silver out of nothing by simply issuing bills of exchange.” "Yes, we can.” Maastricht kept his cool and instructed his men to proceed with the plan.

A network of Wessex bank branches was set up across continental Europe, and the news spread that any bill of exchange issued by the Queen of Wessex is fully redeemable in silver. To make sure the branches were well equipped to handle business, Maastricht instructed his men to fill their coffers with silver. “Just in case”, he said, "there is a desire to redeem the notes for sliver." Maastricht also set up a network of banks and associates across major European trade centers and instructed them to accept any bill of exchange issued by the Bank of Wessex. And low and behold, this time around, the army recruiters had no trouble hiring soldiers and paying them with paper money. In fact, they seemed to prefer that. One recruiter told Maastricht, "I went to a town in the eastern part of Germania and offered them the bills of exchange. They gladly accepted, since carrying silver was dangerous in those parts of the continent.” Soldiers preferred the paper money issued by the Queen of Wessex because, one, it was more convenient, two, it was easily transferable, and third, it was backed by the House of Wessex. In the early days of the scheme, lots of soldiers actually visited the branches and redeemed the bills of exchange for silver. But once word spread that the bills were good and any redemption was met promptly, soldiers opted not to bother with redemption. Soon, other merchants in Germania and Francia (today France) started to accept the bills of exchange for goods and services. In short, Maastricht’s monetary scheme actually worked out. The Queen of Wessex had, almost by accident, invented paper money. And it was a huge success. As more and more mercenaries accepted the bills of exchange, Elisa was able to muster a large army and invade Norway. After only two weeks of battle, King Olaf surrendered and a new king was installed. Norway was to be an independent kingdom with ties to Wessex. Elisa made sure the new king married a distant cousin of hers so that the two royal houses were bonded by marriage. Encouraged by the success of paper money, Elisa instructed Maastricht to set up banking operations around Europe to facilitate trade. Lord Kingston was named chair of the newly formed finance committee that would oversee the issuance of bills of exchange backed by land and silver. Maastricht stayed in the background but profited handsomely, since many of the newly formed branches to support the bills of exchange were part of his merchant banking operation.

As so many things went right for Queen Elisa, she was not only celebrated as the first female sovereign of Wessex but also as its most successful leader. She was particularly interested in helping the poor and underprivileged in Wessex. Thanks to a flourishing economy, the coffers of Wessex were filled with silver, and land prices started to rise again due to a continued influx of immigrants. Elisa established a fund to support the poor. Although the gesture met with resistance amongst the nobles, Elisa’s popularity was such that opposition to her wishes was not possible. Lord Kingston bemoaned the moral conflict such a scheme to support the poor would have in the kingdom of Wessex. “God gave men land and muscles to til the land. If we just pay people not to work, who is going to work the land? This is blasphemy”, he argued in front of the assembly. “Helping the poor is playing god. It’s deciding who has and who has not, a privilege only reserved for God. With all due respect to our Lady Queen, she might be the representative of God in Wessex. But she can’t claim his powers. That is dangerous. The poor are the poor because God wants them to be such. Changing that means changing the natural flow of earthly hierarchies. That is not something humans should engage in.”

His remarks fell on deaf ears with the Queen. But many nobles actually felt the same way. As Wessex guaranteed any man a basic income and paid for housing if he had more than three children, most men decided not to work the land anymore. Instead, they engaged in child production, which led to a large surge in births in Wessex. But as many of those families opted out of the workforce, tilling the land became more difficult. As a consequence, crop yields declined and food prices surged. As Queen Elisa was determined to help the poor, she simply diverted more funds to buy food supplies, build housing, and improve the living conditions of the people of Wessex. Word spread around Europe that the Queen of Wessex “pays men not to work and have children”, which led to an even more dramatic influx of immigrants. This again drove up housing and food prices. And since Queen Elisa was committed to supporting her people, demand kept going up despite the increase in prices. This led to a vicious circle of ever-increasing prices, which again drove the expenses of the court ever higher. Queen Elisa literally became a victim of her own benevolence. Eventually, her coffers were emptied, and Wessex faced a serious shortfall in funds.

Paul Maastricht was summoned to the court to discuss the matter. Unfortunately, Queen Elisa’s health suddenly turned bad, so urgency was required. Lord Pensfield was in charge of filling the Wessex coffers and appointed Maastricht to actually deliver the funds. “Sire, we are in deep trouble. The crown is spending more funds on supporting families and the poor than on any other project. The army is in dire straits, and roads, walls, and ports are neglected. Our infrastructure is dwindling, which is hurting our commerce. Merchants complain constantly. It takes three to four days more to ship goods from Wessex to neighboring Mercia than two years ago. Our kingdom needs help.” As Lord Pensfield delivered this somber assessment of affairs to Maastricht, he stared at him hopefully. “Can you help us?” Maastricht felt the urge to negotiate, but his business acumen and experience guided him otherwise. He stayed calm and assessed the situation. “We must find ways to finance the necessary infrastructure and army to keep Wessex desirable for merchants and finance. We cannot let the kingdom fall into oblivion. Queen Elisa’s generosity is costing her dearly. Even her health is in jeopardy”, Maastricht replied with a business-like tone.

Two weeks later, Queen Elisa died, and her son John was crowned King of Wessex. John was inexperienced and somewhat of a womanizer. His focus was on pleasure and not on fixing the affairs of Wessex. When called to the assembly to discuss the dire situation of Wessex’s financial situation, he would get bored and opt out after only a few minutes. Eventually, he appointed Lord Kingston to fix the issue. “Lord, I don’t want to jeopardize my sister’s legacy. The poor in Wessex must be helped. But I also want to rule over a strong kingdom. I herby appoint you to fix this mess and bring us back to previous glory.” John delivered his speech and immediately retreated to his summer house to celebrate one of his mistresses’ birthday.

Lord Kingston knew what had to be done. He called in Paul Maastricht, who formally presented his proposal of a currency-issuing central bank. “The Bank of Wessex is a good start. But we need more independence. We need a bank that can issue paper currency at will. The paper is backed by the good faith of the King of Wessex. We can't afford to collateralize every note with silver. We simply don’t have enough silver. But if we manage to issue paper currency and float the paper with local merchant bankers, we might just get lucky and create a flywheel effect where money can be multiplied and funds don’t run dry. We might be able to finance the necessary reconstruction of bridges, roads, and ports and, of course, also support the army and the poor. If I am right, this scheme will solve King John’s problems. Lord Kingston was ecstatic and immediately instructed the court’s chamberlain to issue a charter for a reformed Bank of Wessex with new powers to issue paper currency. The fact that not all paper was automatically backed by sliver was to be kept quiet. “People don’t need to know. If they ask, we’ll tell them that the paper is backed by the good faith of King John. Whoever refuses to accept the paper is also questioning the good faith of the King and thereby committing treason. I believe we will be okay." Maastricht wasn’t happy with this subtle threat but accepted it anyway. He had seen how paper money can multiply itself without actual backing before in the Lowlands. Maastricht was convinced that it would work in Wessex, too.

And he was right. The new Bank of Wessex, under the supervision of Lord Kingston, was a huge success. Within less than two years, most merchants accepted bills of exchange since it was much more convenient to do so. Maastricht started a profitable lending business that was backed by the Bank of Wessex. Under this program, Maastricht was able to finance loans by collateralizing them with the Bank of Wessex. When merchants demanded loans for trade, Maastricht would lend them the funds and then immediately turn around and borrow the same amount from the Bank of Wessex, using the merchant’s loan as collateral. Maastricht would collect a fee and also make a margin on the interest rate. “The business works straight as an arrow”, Maastricht would happily explain to his employees. Another innovation was what Maastricht called “land risk transfer”. Under this program, Maastricht would buy up bonds that are backed by land and collateralize them with the Bank of Wessex. This spurred a massive land purchase boom, which of course drove up prices. Lord Kingston, for example, was able to collateralize his land at prices three to four times higher.

King John didn’t show much interest in the economy of his kingdom. "I can pay for what I need. What more do I need?” He would say this in the assembly and then retire. John was not a man of affairs. But he was a man of war. As he got older and married, philandering around Wessex was not an option anymore. So he applied his excess testosterone to fighting. One particular thorn was the kingdom of Francia, today France, where Charles the Great or Charlemagne had established a powerful kingdom. While his successors weren’t as successful on the battlefield, they still commanded much authority. This bothered King John. Wessex was the more successful kingdom by any metric. Whether it’s craftsmanship, infrastructure, or the armed forces, Wessex outshone Francia. But the people of Francia and its rulers didn’t show any respect. So, John decided to use force against Francia. Equipped with a functioning fiat money economy, financing soldiers abroad was much easier. Before Paul Maastricht launched the Bank of Wessex, soldiers were paid in silver, and silver had to be shipped to the battlefield. Now a network of messengers would bring bills of exchange to the relevant branches around Europe and pay the soldiers that way. It was easier, more efficient, and much less costly to raise an army that way. And that’s exactly what King John did. He raised an army to march against the Carolingian Empire, a conglomerate of territories that emerged from Francia during that time.

Unfortunately for John, the attack ended in a stalemate, with thousands of troops stranded around the lands of Western Europe. Paying those troops became a huge drain on John’s resources. But he had no choice. It was either pay and keep the battle alive or accept defeat. “I am not going to cave in. We will pay the troops and stand by for battle. The Carolingians will eventually give up.” King John gave an enthusiastic speech in front of his assembly and rallied the nobles of Wessex to keep supporting him. But there was no money left in the coffers. Wessex was drained of resources. As Paul Maastricht put it during a dinner with nobles, " He wants to support the poor, build roads and ports, and fight the largest empire on the continent. It just doesn’t work like that. You can’t do that. We must convince him to stop the war." But who should do that? Nobody dared to approach King John, who increasingly turned despotic. And so nobody raised any real concern with the King. In order to keep the finances running, the Bank of Wessex just kept issuing bills of exchange to pay for soldiers and other liabilities. Maastricht knew deep in his bones that this was financial suicide. But what could be done? The only way to stop this lunacy was to convince King John to stop overspending. Lord Kingston was chosen to approach the King with an entourage of bankers and suggest a course of action to bring the Kingdom back on track. “Sire, we urge you to consider reducing the financial outlays of the Kingdom. In particular, the war on the continent is costing us way too much money”, they explained. “Ha, money. I thought I control the money supply. Just issue more bills and pay the soldiers. What’s the problem?” King John genuinely believed that the Bank of Wessex had a free pass when it came to spending money. Why stop now? “Sire, we must be careful with the issuance of bills of exchange. The Bank of Wessex has the creditability of the people. But this credibility only lasts so long. At some point it will break, and I fear we could have a panic”, Maastricht explained with a soft voice. “A panic!” John exclaimed. “Why would they panic? The Bank of Wessex issues bills of exchange backed by the full faith of the King. Whoever panics over that is directly challenging the full faith of the King. That is treason. Bring me those panicking traitors, and I will teach them a lesson!” King John was in full swing. "Yes, sir,", Maastricht carefully answered. “Maybe the people of Wessex won’t dare to question your loyalty. But the soldiers in the trenches will. They are foreigners, and if word goes around that the bills of exchange might not be worth what they promise to be, this could trigger mass desertion.” King John took a moment to think about this. “Then we’ll make sure that every solider gets fully redeemed should they choose to present the bills to one of our branches. I herby decree that bills of exchange issued to mercenaries must be fully backed by sliver. All of if!” King John stood up from his chair to make a gesture of dominance with his arms. “The army of Wessex is fully backed by silver.” "But, sir,” Maastricht nervously interjected, “we don’t have enough silver to back all the notes issued to soldiers. Should we do that, we’ll run out of silver quickly.” John’s eyes scanned Maastricht up and down as if he were slapping him every time John’s head changed direction. “You said we can build a flywheel where bills of exchange can be issued and multiplied without full backing. That’s what we did. Now you’re telling me we don’t have enough silver, and that’s a problem. You lied to me.” John exclaimed furiously. "Yes, Milord, we did manage to issue bills in excess of our silver reserves. But now you’re changing the picture. By explicitly backing the bills issued to soldiers, you are also proclaiming that all other bills might not be backed by silver. That will cause a run on our banks. Nobody will be sure what bill is backed and what bill isn’t backed. We can’t allow this to happen.” ”So what do you suggest then?” ”Sire, we must reduce our spending. We must focus our resources on what matters most to Wessex and channel the funds that way. Supporting all the entitlement programs at home and fighting the Carolingians is just not possible financially.”

King John had no patience with Maastricht’s cautious approach to his grand political goals and ordered him banned from Wessex. Within a day, Maastricht was stripped of all his privileges; his funds were seized, and he was sent to the border, where he and his family crossed into neighboring Mercia on a carriage like poor peasants. In the coming weeks, King John rearranged the Bank of Wessex, had most assembly members replaced, and decreed that all sliver available to the crown must be directed towards the war on the continent. As predicted by Maastricht, this caused a panic in Wessex, where everybody stormed the bank branches to redeem the bills of exchange. Unfortunately for King John, the panic was so severe that within days, riots broke out. The King had no choice but to retaliate and execute rioters en masse to send a warning to the rest of the people of Wessex. With no silver left in the coffers at home (all silver was shipped to the continent to support the bills of exchange used as payment for mercenaries) and no paper money that people trusted, King John was literally out of funds. His kingdom collapsed into a primitive barter economy where farmers hoarded food out of fear and sometimes even greed. Wessex quickly descended into chaos, and by the end of the year, King John’s personal guard deserted him. Left with no protection, King John was beheaded by rioters, and Wessex collapsed into anarchy. The war in Francia of course, was lost since nobody trusted anything anymore. Branch managers at the Bank of Wessex subsidiaries around the continent hoarded sliver, knowing that they might never have to account for it with the crown since there was no legitimate King left. Eventually, Mercian soldiers marched into Wessex and annexed the failed kingdom. King John and his dynasty were labeled traitors and condemned as enemies of the people. Ironically, Mercia called back Paul Maastricht back to establish a sliver-based monetary system in the newly formed combined kingdoms. During his meeting with King Arthur of Mercia, the new ruler of Wessex, Paul Maastricht, humbly acknowledged that his monetary scheme didn’t work. “Sire, we thought we could create a system based on paper money and the good faith of the King. Unfortunately, we failed. I therefore suggest we design our new economy based on a silver standard where every bill of exchange, financial note, and any other instrument of credit is fully backed by silver. While the crowds are loyal to the King, they are not going to be loyal to a monetocrat, which is a despot who forces them to accept his money. When it comes to people's livelihoods, only hard money works. You must back your faith with hard silver”.

5. The Solution - Competition

Soft money is toxic for an economy. Unfortunately, the inverse of this statement doesn’t hold either. Hard money is no guarantee for a functioning economy. It helps, but there’s no guarantee. That’s because ultimately, power determines what is and what isn’t. In other words, it’s the most powerful entity in society that has the power (by definition) to either make a society flourish or not. We have the knowledge to design an economic system that fosters prosperity, liberty, and fairness. But do we have the will? That’s the key. While the collective almost always wants to optimize for those three factors, it’s not clear that the most powerful entities in society agree with that. In other words, we need to find a way to design an economic system that optimizes for liberty, prosperity, and fairness while taking into account the perils of power and its corrupting effects. When it comes to money, this is even more important since controlling money is the ultimate power. If you control money, you control the allocation of labor and wealth. The one who controls money has the power to decide who wins and who loses in society. That’s even more power than a king or modern dictator.

As the tale of Wessex shows, controlling money can have corrupting effects and potentially bring down an economy. The US is in a similar position today, with a cabal of central bankers and political operators controlling literally all the money in the world, through the Fed. This is dangerous. What can be done to mitigate the risk of system decline and failure?

We propose a system of competing political entities. The goal should be to foster experimentation with monetary and political regimes. Some of what we have is good, such as the checks and balances between the three powers of the state. But as discussed above, the establishment of the Fed in 1913 and the subsequent introduction of the dual mandate in 1978, followed by Ben Bernanke’s decision to directly interfere in the bond market, have put us on track towards an unchecked monetocracy where few people have the power to decide who wins and loses in the economy. We must stop that. And the best way to stop that is to foster competition among states. Probably the best part of the current US political system is the federal organization in 50 states. Let’s use this to our advantage and introduce more competition amongst states in how they govern themselves and what kind of monetary regime they choose to have.

We suggest more economic autonomy for states in the union. Let’s be clear. We’re not advocating for segregation, since there is a need for a common defense policy. But we can leverage the already federal system of regional power centers and introduce more competition amongst states. For example, let Florida adopt the Bitcoin standard. Let Texas experiment with regional power centers that incentivize energy harvesting on a much larger scale. Let New England elect people like Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren to run an experiment in socialism. And let California pursue a Saudi Arabia-style economic policy where massive wealth is created in one part of the economy (Silicon Valley) and the rest is supported by the state. Let states compete.

6. The Uncertainty Principle of Economics and the Need for Experimentation

The fundamental problem with economics is that its main goals—prosperity, liberty, and fairness—are not perfectly achievable as a collective. We call this the “Uncertainty Principle of Economics”, a concept borrowed from quantum physics and the ‘Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle”. The “Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle” is a fundamental concept in quantum mechanics. It states that there is a fundamental limit to how precisely certain pairs of physical properties of a particle, such as its position and momentum, can be simultaneously known. In other words, the more accurately you know one of these properties, the less accurately you can know the other. The same applies to economics. The more precision you apply to liberty, the less precision you’ll reach with fairness and prosperity. You can optimize for one of these principles, but then you’ll lose on the other two. For example, maximum liberty might infringe on fairness and prosperity. Or maximum fairness will harm liberty and prosperity.

Because of this fundamental limitation, the best course of action is to keep trying. There is a right way to organize an economy. We might never reach it, but we can get better at it. Like in physics, the only way forward is through trial and error. The experiment must be built on theory, then the latter must be revised after the results of the experiment come in and then repeat. Experiments in economics are difficult, particularly in political economy. But it can be done. The solution is more competition and experimentation among constituencies. Questions such as how much power should the executive branch receive or how to deal with poverty have not been perfectly answered, yet. Experimentation will leas to better solutions. Let’s have a centrally governed New England run by Bernie Sanders and a more lax, federally organized Texas. Let’s run Florida as a dictatorship under De Santis and California as a socialist wealth society along the lines of Saudi Arabia. Let’s experiment.

Most importantly, we must keep borders open so people can choose with their feet. If you don’t like socialism, move to a state that is run differently. If you want more inclusion and equity, move to a region that cherishes those values. If you want hard money, move to where money is hardest. Let people choose and find out what suits them best.

There is no one definition as to what constitutes the “right” government. That’s because the right government is subjective. It means different things to different people. Problems like that are best solved through experimentation and trial and error. Liberty must be preserved, fairness observed, and prosperity fostered. Whoever comes up with the best solution for this problem will attract the best people, have the highest GDP per capita, higher living standards, and most likely be more happy citizens.

Conclusion

The US was conceived on the pillars of liberty, prosperity, and fairness. In order to achieve those goals, checks and balances were introduced to the political system. This worked well until the creation of the Fed in 1913. As it turns out, this was a cardinal mistake. Today, the Fed is the result of an accumulation of expedient solutions to immediate problems that have taken a life of their own. As a consequence, our economic system is hijacked by a small group of unelected bureaucrats at the Fed. They find ample support on Wall Street, in Washington, in academia, and in the media. The Fed has the power to issue currency, intervene in the economy, and decide who wins and loses. We call this system a monetocracy. The purpose of this essay is to expose the perils of monetocracy and offer a solution. In order to mitigate the risk of economic decay, we suggest more competition amongst states. The states are already set up as federal entities with sufficient autonomy. Let them take even more autonomy, in particular the choice to apply their own monetary system. We are not advocating for secession but for more autonomy amongst states so they can experiment with policy regimes. In this scenario, we could see regions like New England adopt socialist policies with central banking at their core, while states like Texas or Florida might opt for hard money and less intrusive governments. California might choose the path of a wealthy society with socialism attached to it. Based on the Uncertainty Principle of Economics, we postulate that liberty, prosperity, and fairness cannot be achieved precisely as a collective. But we can find better solutions to optimize for those goals. And the best way to find solutions is to experiment at the state level. Part of this plan is to assure free movement of people and capital so citizens can choose which economic regime they prefer. This is the closest to an economic laboratory for experimentation. While we can’t predict which region will prevail, we are certain that competition amongst states will produce better results for citizens.