Trolley Economics

Economics is the science of solving trolley problems. Disregarding this aspect is either bad science or sophistry.

When Adam Smith published his book "The Wealth of Nations," he genuinely asked a question and then found answers throughout the book. I wish more contemporary scholars worked that way: ask honest questions and look for honest answers. Smith’s book title was actually "An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations." Smith was onto something. Why do some countries do better than others? That was his question. His answer: markets. It’s important to recognize the subtlety here. Smith was not looking for an argument to support free markets. He didn’t even know there was such a thing. He asked a question, and markets sort of dropped in his lap.

Now, "markets" means a lot of things to a lot of people. I won’t go into that discussion here. My aim in this essay is to reframe the economics problem as a generalization of the trolley problem.

I will first describe the trolley problem as it was originally formulated by Oxford philosopher Philippa Foot. The trolley problem is a thought experiment, kind of like Schrödinger's Cat for ethics. Second, I take this idea further and, through examples, show that economics can be seen as the science of finding approximate solutions to a general formulation of the trolley problem. Third, I’ll make a case for a better science of economics, free of demagogues, rent seekers, and pseudo-scientists. Once a problem is formulated properly, genuine questions can be asked and valuable answers obtained.

Fourth, I show that the most important trolley problem is actually inter-temporal. In other words, economics must entertain the question of how to deal with trade-offs between current and future generations. Most importantly, this trade-off is not just between me and my offspring; it also applies to me and my future self.

Fifth, I offer some ideas and thoughts for further research.

The trolley problem and the superposition of outcomes

In her seminal paper "The Problem of Abortion and the Doctrine of the Double Effect," Oxford philosopher Philippa Foot introduced the thought experiment we today call the "Trolley Problem." The actual formulation of the trolley problem with the word "trolley" in it was popularized by MIT philosopher Judith Jarvis Thomson about ten years after Foot published her paper. For the purpose of this essay, we’ll talk about Foot and her formulation of the trolley problem.

In essence, Foot’s thought experiment is in the same class as Schrödinger's cat, introduced about half a century earlier. They both have the same goal in mind: to shed light on some apparent contradictions in science. Schrödinger’s concern was the absurdity of superposition in quantum physics, i.e., that an electron can be in two locations at the same time. In Foot’s case, it’s the superposition of outcomes as a consequence of decisions.

In the case of abortion, a woman might want to abort her pregnancy in order to save her life. Her intention is to save her life, but by doing so, she kills the fetus. Foot calls this superposition of outcomes the “Double Effect Doctrine.” She goes on to list various other scenarios where well-meaning intentions can lead to bad outcomes for others.

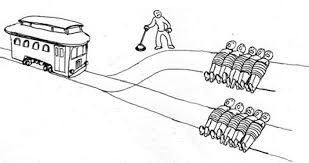

The original formulation of the trolley problem goes as follows:

Imagine a trolley is running at full speed into a valley. Five men are working on the tracks and cannot escape the trolley since the valley is too narrow. You are the driver of the trolley, and you have the choice to turn the trolley to the right and avoid killing the five men. But by turning to the right, you will kill one man who is working on this track and also would not be able to escape. What do you do?

Economics is about finding solutions to a general formulation of the trolley problem

My premise here is to generalize the trolley problem and support the argument that economics is, in essence, the science of finding solutions to a general formulation of the trolley problem. Another way to say this is that if there is no trolley problem, then there is no need for economics. If the trolley driver can stop the trolley without hurting anybody, he should just go ahead and do so. There is no need for further reflection. But what if he can't? That's where the trolley problem kicks in.

What do I mean by a general formulation of the trolley problem? In Foot's case, she was talking about life and death decisions. For example, a patient can be saved by giving her a full dose of an antibiotic, or five patients can be saved by giving each one-fifth of the dose. Which course of action do we choose?

Now, let's generalize this thought experiment. For example, what if we build a hydroelectric power plant in Lake Tahoe? We could support most of Northern California with clean electricity. But we would destroy Lake Tahoe. Or how about shutting down a whole country in order to prevent the spread of Covid? We might save lives, but we might also cause suffering to other people, jeopardize their livelihoods and cause death. Lockdowns prevent cancer patients from getting their mammograms done and jeopardize the education of school children.

Life is full of trolley problems. Some of them have deadly outcomes, some don't. But one thing is for sure: whenever we are faced with trolley problems, somebody will benefit at the expense of somebody else. That's precisely what economics deals with.

The purpose of economics:

Economics is the science of finding approximate solutions to a general formulation of the trolley problem.

Most human decisions have a trolley problem flavor. Fortunately, it's not always about life and death. But for those involved, it's typically serious. Economists have recognized this. In a recent essay, Duke economist Michael Munger interprets Adam Smith's work as a solution to the trolley problem. I agree. In fact, economics can be defined as the science that approximates solutions to a general formulation of the trolley problem. That's where markets and property rights come into play. Whenever you have diametrically opposed incentives and preferences, one way to deal with the problem is to find a price and trade. Another is to start a war. Smith basically urged humanity to stop fighting wars and find ways to trade. That was one of the biggest innovations of the Scottish Enlightenment.

One advantage of having a good definition of a science is to detect when that very science is butchered or hijacked for other purposes. In other words, knowing what a science is also implies knowing when it's not.

I am using the example of Joseph Stiglitz to illustrate my argument. But let's be clear, Stiglitz is just one prominent figure in the club of political sophists who preach their gospel under the disguise of science. On a recent appearance on the Capitalisn't podcast hosted by Luigi Zingales and Bethany McLean, Stiglitz criticized modern capitalism and offered a more collectivist approach towards economics. In other words, he is pushing for a left-wing agenda. What's appalling to me is not his political view. He is entitled to one. But the way he treats economics as a tool to push a political agenda is reckless.

For example, he talks about Covid and how infringing on people's rights through lockdowns is justified because it saves other people's lives. Stiglitz justifies lockdowns with a pseudo-scientific argument of rational trade-off between saving lives and infringing on the rights of others. But he completely neglects the fact that this is a classic example of the trolley problem. In fact, this is the trolley problem. By locking down cities you might save lives of people who are at risk of dying of Covid. But you are also endangering many other lives. Lockdowns brought many small businesses to the brink of collapse, caused depression, loneliness, weight gains and many other unintended side effects. Recognizing this trade-off is the basic job of any economist worth his salt. Denying it is reckless. I call this Trolley Economics.

Stiglitz exemplifies trolley economics. Sadly, he was also awarded a Nobel Prize in Economics, which offers unwarranted legitimacy to his sophistry. In another passage, he talks about unions and how they have the right to protect their interests. Yes. But what about the people who get hurt by unions, such as children whose education was infringed upon by unions refusing to open schools during Covid? How many lives will this cost? Climate change is another favorite of Stiglitz. He advocates for rules and restrictions on polluters. That might be useful, but what about all the adverse effects of such measures on customers, employees, and business owners?

Next time you're sitting in a classroom listening to a seminar, pay close attention to traces of a trolley problem. If there is one, ask yourself whether the presenter deals with it properly. If not, they are either selling snake oil or just not a good economist. I am well aware of the difficulty of finding solutions to most trolley problems. But failing to recognize them is a scientific blunder.

Here are some examples of typical discussions in economics that, when seen through the lens of the trolley problem, might offer interesting solutions. This is very important. Formulating a problem adequately, even if it doesn’t have an immediate solution, is half the battle won. Look at physics. When Erwin Schrödinger formulated the famous cat thought experiment, people thought it was absurd. How can a cat be alive and dead at the same time? But Schrödinger’s insistence on thinking this through led Hugh Everett to formulate the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. Whether you adhere to it is not relevant. What matters is that Schrödinger’s thought experiment eventually inspired new, out-of-the-box thinking. And that's what science is all about.

Now, let’s get back to economics. Here are canonical examples of economics problems that can be reformulated through the lens of the trolley problem.

1. Money printing by the Fed.

As of this writing, the US national debt is approaching $35 trillion. An increasing portion of that debt is being monetized by the Federal Reserve. In other words, the government is spending money that the Fed is printing. Advocates of debt monetization often argue that the Fed “had to act” in times of crisis, such as during Covid relief or the bail out of Wall Street banks in 2008. Another popular argument is that the government must maintain its defense spending and provide welfare to its people. These two budget items alone (defense and welfare) constitute about 75% of the government budget.

How is money printing by the Fed a trolley problem? By helping one constituency, the Fed is hurting others. Why is saving Wall Street banks more important than keeping inflation in check? Why is Covid relief more important than preserving people’s freedom? And most importantly, by issuing debt, we are putting the burden on future generations. When Ben Bernanke decided to monetize the sour mortgage assets of Wall Street banks by using Fed money to offload them from the banks’ balance sheets, his decision implied a superposition of outcomes. Here is a list of the most important certain outcomes that this decision implied:

Wall Street banks will bet spared from filing for Chapter 11.

Wall Street bankers will keep their wealth.

Wall Street failures will be socialized.

New York real estate, private school tuition, and luxury items will increase in price.

Future decisions of bankers will anticipate bailouts and therefore act more recklessly.

US national debt will rise because the Fed will intervene more, due to moral hazard.

Unfortunately, most economists completely neglect the trolley problem aspect of the Fed's actions. Whether they do this out of self-interest to please the Fed or out of ignorance is an open question.

2. Industrial policy

One of the most damaging developments in recent years has been the revival of industrial policy in the US. It started under Donald Trump and intensified during the Biden administration. Industrial policy is an oxymoron. It is supposed to help the industrial development of a country, but in essence, it most likely leads to opposite outcomes because political meddling in industry typically ends up hurting the long-term prospects of a country. For example, through the passage of the IRA (Inflation Reduction Act), the Biden administration supposedly wants to foster the development of an electric car industry in the US. One of the most absurd measures is to subsidize hybrid cars, which are fueled by conventional gasoline and a small battery for auxiliary usage. The subsidy of hybrid vehicles is nothing but a subsidy of legacy car manufacturers and will put the US on the back foot in the race for dominance in the EV industry. Industrial policy is full of such paradoxes. It’s prone to rent-seeking and corruption. Even if you assume well-meaning bureaucrats who are trying to do the best for their country, they suffer from a lack of expertise, information, and most importantly, they completely neglect the trolley problem aspect of their decisions.

The key word here is “neglect”. I don’t expect bureaucrats or academics to have a ready solution for every trolley problem in the real world. But pretending they don’t exist is not a good strategy either. In principle, the trolley problem suggests that decisions have a superposition of known outcomes that must be considered. If we subsidize hybrid cars, we will slow down the development of fully electric cars. We will invest less in research and development of EVs, slow down progress in this area, and fail to inspire young people to pursue relevant career paths. Those are known outcomes. They are in superposition with the intended outcomes of helping legacy car manufacturers sell more hybrid cars. One decision has multiple outcomes. It’s literally the economic policy version of Schrödinger’s cat. Your policy is both helpful and harmful at the same time. All I am asking is to recognize this fact and think about solutions accordingly.

Let’s say the US decides to develop a nuclear power industry like in the 1950s. That might be a good idea. But it comes at a cost. Alternative energy technologies will not be developed. People will suffer from risks and sometimes even death through nuclear accidents. Nuclear power plants can be used by terrorists as Trojan horses, as Russia threatened to do by potentially destroying nuclear power plants in Ukraine. When decisions of this magnitude are made by politicians or unelected bureaucrats, we must consider the known counterfactuals. This is not just about unintended consequences or unknown unknowns. It’s about balancing the pros and cons of known outcomes, similar to how the trolley pilot must weigh whether to divert the trolley or not.

My objection to industrial policy is simply the fact that it doesn’t work. It has never worked before, and it will not work in the future. That's because it's too complex of a problem. Neither bureaucrats nor politicians are trained to solve complexities with trolley problem-type implications. Hence, crowdsourced solutions such as political or monetary markets promise a higher likelihood of success. Instead of wasting our time drafting industrial policies, we’re much better off working on better market designs so that solutions can emerge organically.

3. Minimum wage

Here is a favorite topic among economists: the debate over minimum wage. At first glance, minimum wage feels beneficial. It provides a minimum income to blue-collar workers and improves their standard of living. However, by doing so, it disrupts the workplace and makes it harder for young and inexperienced people to enter the job market. In reality, minimum wage is primarily designed to protect incumbents and limit competition in the labor market. If that is the desired policy, then let’s call it what it is: "protection of incumbent workers against competition from younger people or foreigners."

Viewed through the lens of the trolley problem, minimum wage raises the question of whether you want to help an incumbent and simultaneously hurt younger, inexperienced people or not. This scenario exemplifies the classic double effect, to use Philippa Foot’s terminology, where helping one group results in hurting another.

4. Licensing of professionals and academics

Here is another classic example: licensing doctors, lawyers, pilots, real estate agents, or psychiatrists. Licensing feels like the right thing to do, but as in the minimum wage example, it disrupts industries and hurts people as much as it helps others.

The typical argument for licensing is: “we have to ensure that someone is educated enough to provide a service. Without licensing, customers could be exploited by charlatans.” This argument may have merit, but let’s also consider the costs of licensing through the lens of the trolley problem. Licensing protects the reputation of one group (licensed professionals) at the expense of another (unlicensed individuals and customers who might prefer their services). Licensing restricts the choice of service providers and inevitably leads to higher prices. Inflation is almost guaranteed in any licensing system, whether in healthcare, real estate, or aviation. Even worse, in many cases, the inflation does not benefit the workers but only enriches the institutions that provide the licensing. Ultimately, licensing only benefits the licensor, which in most cases is a select few unelected bureaucrats. Take pilots, for example. They often do not earn substantial incomes, and the costs associated with obtaining and maintaining licenses can significantly strain their finances.

A much more serious example of licensing abuse is academia. Top universities charge exorbitant fees to "license" graduates. Cost inflation in academia is a significant national problem in the US and affects everyone, including the wealthy. It's a troubling example of how licensing policies contribute to monopolistic situations and price inflation.

Sal Khan, in my opinion the most inspiring thinker in education, has called for a universal accreditation system to allow people to acquire knowledge and secure jobs without having to navigate the prohibitively expensive and exclusive academic system. See my essay on "Peak Academia" for more on this topic.

Licensing can be viewed as a general form of the trolley problem. By licensing a pilot, I protect her integrity at the expense of other pilots who are equally skilled but lack a license. I compel the latter group to bear the costs of obtaining the license. Similarly, in academia, by licensing undergraduates or PhDs, I grant them credibility but disadvantage others who lack the means to acquire the same credentials yet possess the knowledge.

Moreover, we harm society by increasing the cost of the licensing process and potentially contributing to inflation.

In some cases, licensing actually results in absurd outcomes where licensed individuals are less qualified than unlicensed candidates. Academia is a prime example, as increasing numbers of graduates are perceived to be less prepared for roles in productive companies. This has prompted prominent businessmen like Peter Thiel and Elon Musk to advocate for dropouts and alternative paths to education.

5. Saving versus consumption

One particularly interesting application of the trolley problem is when it deals with one person only, but at different times. When deciding whether to buy a Porsche or save the money for later, you are facing a version of the trolley problem: give pleasure to person A (present self) at the expense of person B (future self), or let person A forgo pleasure for the benefit of person B (future self in 10 years). Imagine a gigantic matrix with many versions of the same person in different time slots and under varying conditions. Now, envision all those persons negotiating an optimal course of action.

In traditional economics, saving is often explained in terms of trade-offs between inter-temporal consumption anchored by interest rates. In this model, the interest rate is the price of money and therefore provides individuals with a gauge of how much they should spend today and/or save. But this is akin to giving health advice to a person and telling them to watch their temperature. A steady temperature is a consequence, not the actual goal of good health. The same applies to interest rates; they are a consequence and not the primary concern. What we truly care about are preferences and decisions.

My conjecture is that framing the savings problem as a trolley problem will yield much better results. Imagine a world where the US is divided by the Rocky Mountains. The East approaches the world as we do today. In contrast, the West has adopted a Philippa Foot-type worldview where everything is considered through the lens of the trolley problem.

What I am suggesting is that the West would perform much better economically, socially, and individually than the East. That's because people in the West would devote more time to contemplating inter-temporal decisions and grappling with trolley problem-like complexities, which optimize for long-term success.

Instead of hiring an army of bureaucrats to design industrial policy, the West would dedicate more time to designing markets for each substantial trolley problem they identify. In this hypothetical scenario, the West would not have locked down the economy during Covid, closed schools, or appointed a single so-called expert to influence decisions about vaccines. Moreover, the West would be more conscientious about the exploitation of natural resources and finding ways to hold oil companies accountable for environmental damage. Trolley problems are inherently bipartisan.

The Federal Reserve trolley is steering right into the abyss

The ultimate trolley problem, however, is the 800-pound gorilla that nobody dares to talk about in economics departments: the Federal Reserve. Since its inception, the country has accumulated a staggering $35 trillion in debt and counting. What's even more concerning is that most of this debt has been accrued in the past decade. This represents a looming social and economic train wreck. All this debt has been accumulated to meet immediate needs, whether it's for Covid relief, wars, or social welfare. We are saving contemporaries at the expense of future generations. Interestingly, Philippa Foot’s initial motivation when formulating the trolley problem was to address inter-generational conflicts, such as that between a mother and her unborn child.

Inter-generational thinking is not merely an extension of economics; it is economics itself. The purpose of society is to leave a better place for its offspring, and economics is the science that helps us achieve this goal. That’s why the trolley problem is the best framework to consider this issue.

Let’s look at the history of the Fed and analyze each step through the lens of the trolley problem.

1. Establishment of the Fed as an insurance system for Wall Street banks in 1913

In his fascinating book "America’s Bank," author Robert Lowenstein tells the story of the foundation of the Federal Reserve System. He guides us through the labyrinth of political quarrels, pork barrel politics, and the eventual establishment of a central bank in the United States. What’s striking about the Fed's foundation story is the strong opposition it faced from various political groups. Rural states feared that New York finance would gain undue power over their livelihoods and agricultural fields. Patriots were genuinely concerned that the spirit of the USA would be undermined by bankers in New York. Opposition to the Fed spanned across the political spectrum, all sharing a common theme: the fear of Wall Street gaining excessive power at the expense of the rest of the country.

The ultimate reason bankers and politicians pushed for the establishment of the Federal Reserve was to provide an insurance policy to banks and prevent the boom and bust cycles that led to bank failures.

Viewed through the lens of the trolley problem, the establishment of the Fed can be seen as prioritizing a group of Wall Street bankers at the expense of everyone else. It represents a concentration of power in the hands of a few selected bankers, justified by the belief that large-scale capitalism benefits the broader economy. Unsurprisingly, most people outside the inner circle of Wall Street opposed this idea. This opposition was significant enough that proponents of the Fed had to convene in a secret meeting on Jekyll Island off the Georgia coast to finalize the draft for its establishment.

In my opinion it was also the naiveté and delusion about realpolitik of President Woodrow Wilson that helped push this ill-fated project through the ranks of Washington. Had there been a leader with more resolve in the White House, this might not have happened.

Here is a list of trolley problem issues at the time of the establishment of the Fed

Creating a safety net for Wall Street banks favors them over other banks.

Monopolizing money gives undue power to Fed bureaucrats and stifles competition.

Prevents the emergence of potentially better financial system mechanisms.

Increases the risk of corruption.

Raises the likelihood of wars if the government controls the printing press.

2. Dual mandate of the Fed established by Congress in 1977

It’s noteworthy that some of today's most pressing problems, such as high government debt and inflation, would not have been possible under the original regime of the Fed at its foundation in 1913. Back then, people recognized the dangers of central banking and took steps to insulate the system from its most damaging consequences.

Two key factors kept the Fed in check initially. First, there was the gold standard, which technically constrained the Fed from printing money indiscriminately. Second, the Fed operated under a clear mandate of price stability. Even without the gold standard, the Fed was legally obligated to keep inflation under control.

All of this changed in the 1970s. Under budget pressures from the Vietnam War, President Nixon decided to take the US off the gold standard. However, the real blow to the financial health of the US came in 1977 when Congress established the dual mandate of full employment and stable prices as an amendment to the Federal Reserve Act. Prior to this, stable prices were the sole objective of the Fed. By introducing another objective—full employment—Congress effectively opened a Pandora's box.

In practice, full employment became an ill-defined goal with ambiguous measures. This change gave unelected bureaucrats in Washington significant latitude in justifying money printing. Essentially, the dual mandate provided a broad job description that could be exploited. It allowed for the creation of policies that could be used by various interest groups in Washington. In other words, the dual mandate invites people to take advantage of the Fed.

Centralized power is problematic enough, but the real blunder in 1977 was blurring the lines of that power. Human nature predicts that in such circumstances, power will inevitably be misused, profiteers will gain, and the rest of society will lose. That’s exactly what happened. Inflation in the US surged in the 1970s and has continued to rise steadily since then.

As a side note, inflation has significant implications for many people. One effective measure of inflation is the price of the house you wish to live in—whether it's an actual property or a hypothetical dream home—and observing its price in US dollars. I would argue that true inflation in the US since the 1970s has been around 7% per annum, roughly equivalent to the increase in the price of gold during the same period.

Trolley problem issues with the dual mandate in 1977

Favor current workers at the expense of future generations.

Subsidize current industries at the expense of future technological development that could benefit future generations.

Increase corruption and/or pork barrel spending in Washington at the expense of a less corrupt and more transparent political system that future generations would inherit.

Incentivize bureaucrats at the Fed and Treasury to overstep their powers at the expense of regular citizens.

Harm the competitive edge of US industry at the expense of future US workers who may not have opportunities in manufacturing due to the decline of the industry.

3. Quantitative Easing. Ben Bernanke goes rouge in 2008

The financial crisis in 2008 was a watershed moment for global capitalism. I’d argue it was the beginning of the end for liberal democracies and capitalism. Freedom of choice and the free flow of capital are two sides of the same coin. If you centralize one, you are also constraining the other. When Bernanke decided to bypass Congress and buy mortgage-backed securities directly from banks in order to save them, he fired the first shot to kill liberal democracies.

When the financial crisis hit in 2008, all Wall Street banks were technically insolvent because their assets couldn’t cover their liabilities. This was a consequence of reckless lending to real estate projects around the world. Books have been written on why this was even possible. In short, it was irresponsible profiteering by investment bankers who privatized gains and socialized losses thanks to the implicit bailout insurance offered by the Fed.

Then-Fed Chair Ben Bernanke faced a massive dilemma. His job was to keep Wall Street afloat. But prior to 2008, this meant keeping interest rates in check with the economy. The Fed was never supposed to intervene directly with balance sheets and save banks. Nobody ever gave that power to the Fed. Even its most ardent proponents wouldn’t go that far. Bailing out banks was a job for Congress. But Congress could not act fast enough in 2008. The very design of Congress as a pillar of democracy requires time-consuming debate to reach compromises. But in 2008, there was no time. Or so Bernanke thought. Large banks like Citigroup, Bank of America, and others had to be saved or let go to bankruptcy within days. That’s why Bernanke decided to just buy assets from them and save them from going under. This seemingly small step by the Fed was actually a giant blunder. Once bureaucrats opened the Pandora’s box of saving private companies, the key element of self correction by market forces was taken off the table. In my opinion this was the beginning of the end of free-market capitalism. Unfortunately, this rather bleak outlook has played out almost precisely as predicted. Right wing demagoguery started in earnest with the first election of Donald Trump only eight years after Bernanke’s original sin and later spread across the world with nationalist parties gaining ground in Europe and even more centralization in China and Russia.

Just as a side note, we are not advocating that the Fed should have just let everything collapse in a pure laissez fair type manner. They could have nationalized Wall Street banks, fired or jailed incompetent bankers and returned the recapitalized banks to the market. It would have cost much less money. But most importantly, it would have set the tone for future generations of bankers to act more like business men and not like overpaid bureaucrats with a license to gamble.

Trolley problem issues with Bernanke’s decision to save Wall Street banks in 2008

Benefit bankers at the expense of the public.

Set a precedent for monetizing debt at the expense of future generations.

Reduce the credibility of the Fed at the expense of future generations.

4. Federal Reserve monetizes US debt during Covid response

Act Four of the destruction of financial capitalism occurred when the Fed agreed to monetize trillions of dollars for COVID relief. In hindsight, this was the most frivolous act of financial vandalism ever recorded in human history. Trillions of dollars were wasted on what politicians and bureaucrats dubbed “COVID relief.”

Imagine a meeting between powerful men and women in an office in Washington, D.C. Public health officials are scaring them with terrible news about a pandemic that no one seems to understand properly and that is threatening lives. The options are to take a risk and let the pandemic evolve as other pandemics do—people get sick, slowly build immunity, and eventually fight the virus—or to lock down the economy, spend trillions on relief packages, and receive immediate praise for not letting innocent people be killed by COVID. The reason they went for the latter option is because there was somebody ready to pick up the tab.

That somebody was the American people who, represented by an aging lawyer-bureaucrat elevated to Fed chairman, decided to print all those trillions of dollars and distribute them to whoever spread their hands to receive them. Of course, nobody actually made a conscious decision to let Fed Chair Jerome Powell make such a decision. But he did it anyway. Powell backed a plethora of devastating policy decisions that culminated in trillions in deficits, a ballooning U.S. national debt, inflation, frustration, and a massive polarization of U.S. politics.

Spending trillions of dollars on Fed relief is not just a general version of the trolley problem; it is the trolley problem magnified. By monetizing all this debt, Powell decided to favor current rent seekers over future generations. Even worse, he opened another Pandora’s box. This frivolous act of bureaucratic overreach has opened the doors for future bureaucrats to ask for even more money for whatever cause they claim to be fighting for.

As a consequence of these actions, we are now sitting on a massive U.S. national debt. Our government deficit is ballooning, inflation is rampant, and frustrations among the population are rising. The only way out of this impasse is for states like Texas and Florida to take matters into their own hands and create separate constituencies with sound finance, transparent policies, and, most importantly, accountable bureaucracies.

Solutions for the trolley problem

What does it mean to find a solution to the trolley problem? In the original case of the trolley racing down a track and threatening to kill workers, there is no perfect solution. It’s like a linear equation with more variables than equations; you just won’t find a definitive answer. Some people are inclined to choose to kill one person versus five. But, like any other attempt to solve the trolley problem, this approach is short-sighted. In a society like that, people would always choose to work in groups. If more lives are simply valued more than fewer lives, strange behaviors would occur.

Philosopher Philippa Foot tried to approach the trolley problem from the perspective of intent. Her argument goes something like this: if you intend to kill somebody, that’s not okay. But if you kill somebody with the intent to save somebody else, that might be tolerable, but only if you don’t intend to kill the other person. In my opinion, this is philosophical pedantry and doesn’t serve a practical purpose.

So what can we do? What should the trolley pilot do? What should the next Anthony Fauci do? What should the chairman of the Fed do?

Let's start with the easy answers. Fauci, Powell[,] and most other bureaucrats should simply dismantle their institutions because that's where the problem lies. It's not that Fauci was especially evil. The problem is that he had way too much power and should never have been given this much discretion over decisions he was neither trained nor elected to take. The same applies to Fed chair Powell. Nobody taught him how to make a trolley problem decision about whether to spend five trillion dollars to save Covid lives or save future lives that will be affected by this frivolous act of financial decision-making. Institutions are like mathematical variables. They are artificial constructs that help us solve future problems. In order to be useful, they must be crafted carefully and serve a special purpose. The Federal Reserve or the National Institute of Health (NIH) are ill-conceived institutions. They must be redesigned. Explaining how is beyond the scope of this essay. All I can say here is that I believe in a federal solution to this type of problem. We need more state-driven experimentation, more alternatives within the US where individual states experiment with new institutional design. My conjecture is that the state with no or only a rudimentary central bank with clear guidelines, limited power, and no monopoly on money will do much better economically.

Now, let's get to the question of how to tackle real trolley problems that organically arise from voluntary interactions of people.

Let's assume we have a government which is considering borrowing money for the creation of a space exploration industry. Should this be done? What are the implications for future generations of this money spent today?

Here is the situation:

Government A is going to borrow money to build a space industry.

Future generation B is going to have to pay back this debt.

Both parties, A and B have rights. A has the right to issue debt and build infrastructure and B has the right to oppose the obligation to pay back the debt.

Let’s assume future generation B takes government A to court and disputes the debt issuance. How would both lawyers argue? Here is an excerpt from this hypothetical hearing:

Lawyer A represents government A

Lawyer B represents future generation B.

Lawyer A: "Your honor, we are here to make the case for building a space industry. For this, we require a debt issuance of roughly 10% of GDP. We have three arguments for why this should be done. First, we believe our country must keep up with global competition in conquering space. If we don't do it, others will. We must have a seat at this table. Second, we argue that building the infrastructure today is feasible because we have the technical know-how. And third, we argue that issuing debt repayable by future generations is the best way to finance this project because future generations will benefit most from this endeavor."

Lawyer B: "Your honor, we are here to make the case that issuing debt repayable by future generation B for the creation of a space industry is not the right path forward. We also make three arguments for our case. First, we disagree with the argument that building a space industry today is the best course of action. Second, we believe that it would be wiser to invest the money in more research into space exploration and propulsion technology, in order to have a better chance to conquer space in the future. And third, we are of the belief that the financial burden of these investments into the future should be split in half between today's generation and future generation B."

I am fascinated by the idea of giving future generations rights. It's kind of like a Magna Carta issued by today's generation for their own future self as well as their offsprings. This is obviously a complex situation. But the basics are simple; you give your own future self the right to influence decisions made by your own present self. How would Philippa Foot's abortion question change if the unborn child had a say in the situation? I am writing a short story to better illustrate this type of situation. It's loosely related to the Terminator narrative, where a humanoid robot is sent from the future to influence decisions made by contemporaries. My initial draft describes events around a hypothetical pandemic that leads to enormous spending and debt issuance by the government. The humanoid robot is sent from the future to argue against loading such a financial burden on future generations.

In essence, the trolley problem and its economic corollaries all come down to property rights. Assigning rights and responsibilities to the various actors yields better outcomes. It's like every other situation in life where people make decisions affecting each other. Any optimal solution requires the affected parties to have a seat at the negotiating table. Giving property rights to future generations opens the question of what a person actually is. What is a person? What are his boundaries. Does she start with birth, or with conception or with the intent to conceive and does it all end with death? Or is there a continuum through future generation. While the original Magna Carta clearly defined a person as the physical presence of a human being, this notion must be reconsidered trough the lens of the inter-generational trolley problem.

Does your future self have rights today? Can you go to court and accuse the Fed of harming your future self in ten or twenty years? And what about your offspring? Do they have rights? Can your offspring go to court today, represented by a lawyer, and sue you for harming them?

Merriam-Webster defines property rights as "a legal right or interest in or against specific property". Other definitions circle around the legal relationship between people and things and make the case that something belongs to a person. This is key. The life of an unborn child belongs to the child, not the mother. But the mother has the power to end it. This is a conflict, and Philippa Foot described it in her original trolley problem paper.

The same applies to future generations whose property rights are being infringed by contemporary debt issuance. If we load up $35 trillion in debt today, future generations will have to pay it back one way or another. This is an infringement on their property rights. The humanoid robot in my short story will argue in court against spending trillions of dollars on pandemic relief because his generation doesn't want to be taxed with this kind of burden. He will urge the court to block the spending package and ask bureaucrats to come up with better and more sustainable solutions to the pandemic problem.

Property rights

Property rights have an uncanny usefulness to solve real-world problems. It reminds me of Eugene Wigner's classic about the unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics in natural science. Wigner talks about mathematical concepts and their uncanny ability to solve real-world problems. Physical systems are often described in terms of probability distributions. For example, the speed of particles in a gas is not a deterministic entity but a distribution of probable outcomes. Some particles have more energy, others less. The average is what we observe. Water molecules are liquid at room temperature because the average energy of H2O at 25 degrees Celsius is neither high enough for vapor nor low enough for ice. But there are particles that exhibit these types of energies even at room temperature. My point here is that physics is often described in terms of probabilities and probability distributions have the symbol π in them. Wigner asks a simple question: what does π (the ratio of circumference to diameter of a circle) have to do with water molecules? Mathematics offers solutions in areas one wouldn't expect. Its usefulness is even more uncanny when you look at concepts like the imaginary number, where the square root of -1 is i. Erwin Schrödinger derived his seminal formula with the help of i. But what does the evolution of quantum particles have to do with the square root of -1? Wigner's essay is one of those rare pieces of writing, where a simple question leads to amazingly profound insights. Despite the complexity and randomness of nature, there is structure and this structure is precisely what mathematics helps uncover.

I see property rights along the same vein. Human relationships are complex and random in principle. But there is structure, and property rights shed light on that structure. And most importantly, property rights don't just explain relationships between people. They also help predict behavior. That's different from mathematical concepts in physics. Mathematics helps explain relationships between particles. But it doesn't alter their behavior. Property rights do. Human behavior is almost exclusively predicated on property rights. In other words, the design of property rights has more explanatory power than any other variable governing human relationships.

Here are some examples to illustrate the explanatory power of property rights.

The tragedy of the commons

Often used by economists as the canonical motivation for property rights, the tragedy of the commons says more about what happens in the absence of property rights. Imagine a lawn full of green grass, surrounded by farmers. Each farmer wants to have their sheep graze on the lawn. In the absence of property rights, farmers will let their sheep graze as much as they can. Nobody will take care of the lawn, and most importantly, nobody will assign quotas for grazing time slots. In the long run, the lawn will be overgrazed and eventually deteriorate. The tragedy of the commons says that even though nobody actually wants to kill the lawn, in the absence of property rights, the collective action of farmers will lead to a bad outcome.

Now, imagine a world where the lawn is split into parcels and each farmer owns a piece of the lawn. It's highly likely that under such a regime everybody will do their part and collectively the lawn will be taken care of. Nobody will overgraze and some farmers will even get together and build irrigation systems to improve their yields.

Property rights don't guarantee a positive outcome. But it's fair to assume that under the regime with property rights the long-term health of the lawn will be maintained while in the absence of property rights, the lawn will most likely deteriorate.

2. Government debt

The problem of government finance can be seen through the lens of the tragedy of the commons. Think of the total amount of resources available to a society over three generations, which is about a century. This amount, let's call it X, is the lawn. Citizens can use X for immediate consumption, investment or not use it now and save for the future. In the absence of property rights, dynamics like in the tragedy of the commons will take over. People will start grazing indiscriminately and the lawn will eventually collapse. In government finance terms, this means that there will be too much immediate consumption. The resources of society will be wasted. Contrast that with a society where property rights are assigned, even for future generations. It's predictable that the society with property rights will use the available resources much more carefully and therefore have a much better outcome long-term than the society without property rights. This is one of the main reasons why totalitarian regimes don't survive and property rights-centric democracies outshine any other form of government.

3. Healthcare

Property rights are a reciprocal relationship between people and things. Take healthcare. On the one hand, you have autonomy over your personal health, on the other hand, you also have a responsibility to maintain it. This balance can be disrupted. Government-sponsored healthcare often suffers from exactly this problem. People strongly believe in having control over their own health, and rightly so. Nobody has the right to hurt another person or influence their health without consent. But having something comes with responsibility. People also must invest in their own personal health. If an obese person shows up at the hospital and requires treatment for various side effects of obesity, the health system carries the financial and societal burden, regardless of the circumstances that led to this event. The same applies to people who fail to exercise or eat healthy. Sometimes it's not even their fault. Soda and snack companies' products are heavily marketed and widely available, contributing to health problems. They are not necessarily liable for the damage.

Most public healthcare systems can be susceptible to a "tragedy of the commons" scenario. While personal health is individual, the healthcare system functions as a shared resource. When people utilize it heavily, they might not fully consider the long-term sustainability of the system. This can lead to issues like service quality decline, extended wait times, and high overall costs.

Predictive Power of Property Rights in Healthcare

Consider two countries, A and B, to illustrate the impact of property rights on healthcare.

Country A: This country has a system similar to most of the Western world, with asymmetric property rights. Individuals control their personal health decisions, but the financial burden of the healthcare system is shared by everyone.

Country B: This country has a radically different system with full property rights applied to healthcare. Citizens own their health and are fully responsible for the associated costs and benefits. A healthy lifestyle is rewarded with lower insurance rates and treatment costs. Conversely, unhealthy choices may still allow access to the healthcare system, but with higher costs or longer wait times. This system incentivizes healthy behavior through a system of rewards and penalties.

This comparison highlights how property rights can influence healthcare. Country A prioritizes access over individual responsibility, while Country B emphasizes personal accountability for health outcomes.

It's possible to predict that in the long run, system B will most likely outperform system A. Incentivizing healthy behavior should in principle lead to a healthier population and potentially lower overall healthcare costs. This will make system B more financially sustainable in the long term.

Property rights and the trolley problem

Wigner’s essay opens a Pandora’s box that few scientists are willing to accept. Is it possible that mathematics offers just a small lens into the real world and thus gives us the illusion we understand much more than we actually do? Is mathematics fooling us?

There are fields in science where mathematics, at least up to our current knowledge, is insufficient. Examples are consciousness, biology and even some areas of physics such as astronomy or quantum physics. It looks like biology is much better explained with neural networks than with the language of mathematics. Neural networks are function approximators. They use math but math is not the explaining factor. In physics scientists struggle with the explanation of entanglement. How can it be that two particles, lightyears apart, can share information instantaneously? Mathematics fails to explain this phenomenon. Consciousness suffers from similar limitations. In fact, some scientists argue, that because science is so math focused, solutions to the problem of consciousness are almost impossible to find. We need a better language for such concepts.

Property rights have a similar feel. As discussed above, they offer strong explanatory power for many societal problems. But do they really help solve the trolley problem? Let’s assume we give a fetus rights and have it represented by the most prestigious law firm in New York. What can they really achieve? Can the preferences of the mother and the fetus ever be reconciled? How about the government debt problem? Is it possible to convince a senator whose state is about to lose jobs because of factory closures not to subsidize those industries with borrowed money? Humans seem to be suffering from a deep internal paradox. On the one hand, we are hardwired to care about ourselves and our offspring. On the other hand, we seem to completely disregard their well-being and our own when it comes to trolley-problem-type situations.

My conjecture is that humans actually don’t care as much about their own benefit as we think. Just look at their actions. The US has accumulated $35 trillion in debt and counting. Nobody cares about the burden this puts on future generations. And if you think we are selfish beings with our own selfish benefit as the north star, just look twice. How about all the junk food people are consuming? Would they eat poison if they really cared about their own health in the future? Or look at how people, particularly wealthy people, are educating their kids. Americans encourage their kids to play multiple sports and do all kinds of mildly ridiculous activities just to please an arbitrary college admission officer. Compassion and athleticism have been turned into a currency redeemable for admission points to the Ivy League. What about excellence, deep domain knowledge, courage, relationships, and proficiency in finance? Those are skills that eventually lead to positive outcomes. But instead of teaching their kids those skills, most people optimize for the increasingly absurd college admission curriculum. My point here is that property rights are predicated on people doing the right thing for themselves. But what if they don’t? We might need a better theory of human behavior.

Conclusion

The purpose of this essay is to shed light on what we call “Trolley Economics.” Economics is the science of finding approximate solutions to a general formulation of the trolley problem. Disregarding this or, even worse, applying the trolley problem only one-sidedly is pseudoscience and often dangerous. Trolley economists are often political operators disguised as scientists, preaching their gospel under the umbrella of pseudoscience. Economics is particularly prone to such behavior because its subject matter often touches money and wealth. We show that disregarding the trolley problem leads to negative and often absurd outcomes in economics. Most trolley-problem-type situations don’t have perfect solutions. But recognizing them and working on approximate solutions lead to better outcomes for society. One promising approach toward solving trolley problem dynamics in society is the assignment of property rights. Markets are a corollary to property rights and act as solution approximators. Instead of wasting resources on industrial policy, societies are better served spending more time and energy on property rights and market design.